For many Americans, a week without driving is just a regular week. Each morning, they get up and decide how to get to work or school. They use bus schedules, ride-sharing apps, and their favorite mapping software to negotiate how to pick up groceries and how to get their kids to soccer and dance. Depending on where they live, these decisions may not be difficult — or they may mean hours spent waiting outside in the rain, forgoing basic needs, and even risking personal safety.

Life without a car is a challenge in the United States. And those who do drive, who have access to a vehicle when they need it, those challenges may often go completely unnoticed.

That’s why Disability Rights Washington and the Disability Mobility Initiative challenged local leaders, including lawmakers, to participate in the first-ever Week Without Driving.

“My biggest takeaway is how exhausting it is”

In an interview with the Everett Herald, Washington State Rep. April Berg, D-Mill Creek, reflected on the necessary changes she had to make in order to maintain her schedule, which included meetings with constituents across her district.

From the Herald:

When she wanted to get groceries, Berg had to scale back her shopping list. A back injury from a car crash last year scuttled carrying her usual haul home from the bus stop.

When she had meetings in Everett and had to be in Seattle in the same day, Berg shifted an appointment to align with the bus schedule to take her south.

The frequency of that route helped her. But not every route in the county has a bus ready every 15 minutes, and she said transit service closer to 10-minute frequency would help people.

Seattle’s Department of Transportation Director, Sam Zimbabwe, said that while he walked often and used transportation, he did end up having to drive out of necessity.

“Each of my unavoidable car trips during the week involved the kids,” he told the SDOT blog. “One drop off at school when my wife had to go to her office, and one soccer practice. We did manage to carpool to a soccer game and a practice, while I biked. Both of these trips could have been accomplished on transit, but would have taken a long time (up to an hour longer than a 10-minute car trip).”

Zimbabwe said one reason the week was especially challenging was that he coaches soccer practice, meaning he had “balls and equipment to haul to twice a week practices and a weekly game.” This level of involvement in his kid’s athletics would be nearly impossible without regular use of a car.

Other decision-makers explained that not driving made family time more difficult, and that many of the daily activities they take for granted became much more time-consuming and even impossible.

More than a week without driving

These are not surprising findings to those in who don’t drive. What may surprise transit-users, though, is that the Week Without Driving did earnestly shift the perspective of at least one lawmaker. Berg told the Herald that her experience has convinced her seek more transit funding and resources for more sidewalks.

The Week Without Driving may not have massive national implications — but it does demonstrate how much organizing and activism can lead to shifts in perspectives by those in power. By asking that decision-makers spend a small amount of time experiencing the same challenges and struggles as those who don’t drive navigate every single day, Disability Rights Washington created a paradigm shift for many.

Read more about the Week Without Driving in the Stranger, the King County Metro blog, and the Seattle DOT’s blog.

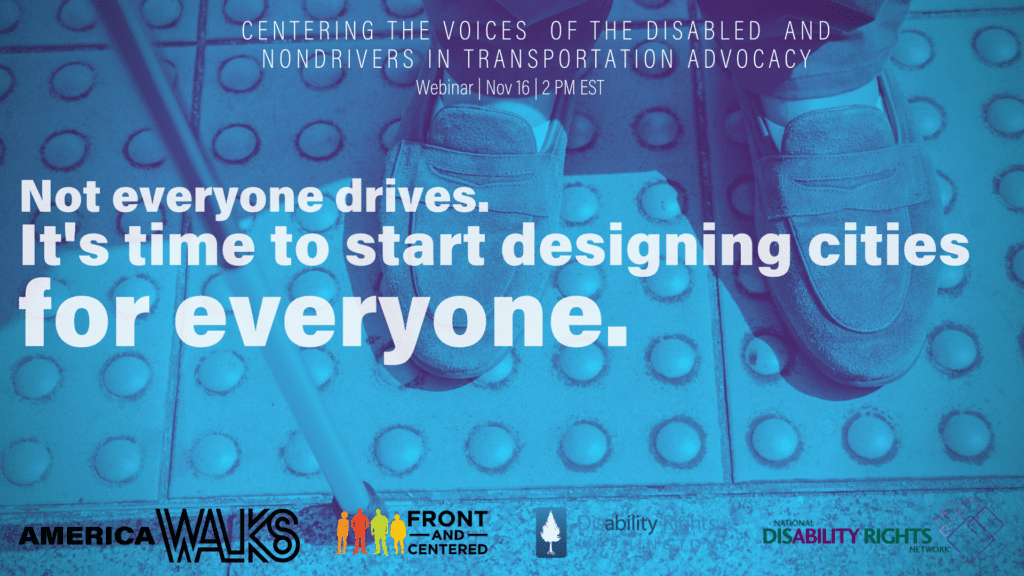

And if you’d like to learn more about nondrivers and how they’re advocating for improvements in their own communities, join us for our webinar on November 16.