Eleven local walkable community advocates from the fifth lowest-population state in the country graduated last week from the South Dakota State Walking College.

Since the program launched in June, these Fellows have worked their way through the Walking College curriculum – consisting of six learning modules, dozens of articles and online materials, weekly discussion sessions, community activities, and a written Walking Action Plan!

One new assignment this year, based on the teachings of former United Farm Workers organizer Marshall Ganz is to develop a “Public Narrative,” in which the Fellows tell their personal “Story of Self,” an outward-focused “Story of Community” about their allies, and a “Story of Now” describing an urgent problem which needs to be solved.

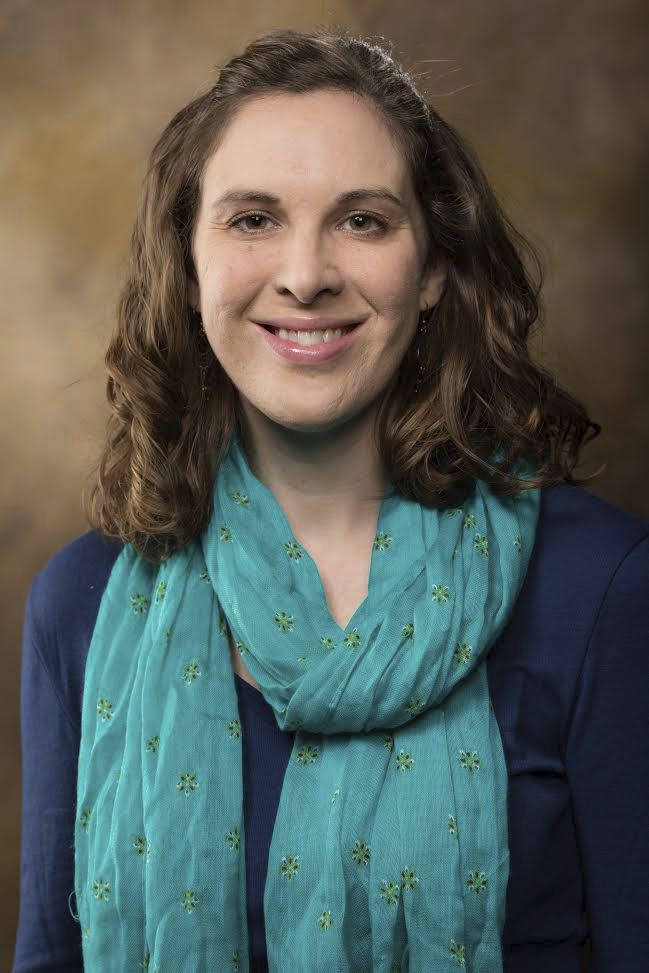

Get to know two of these incredible advocates in their own words. These “Stories of Self” were written by Prairey Walkling, who supports Native American communities in her role as a Family and Community Health Field Specialist with South Dakota State University Extension; and Chrissy Meyer, who works for the American Heart Association in Sioux Falls.

Prairey Walkling

Family and Community Health Field Specialist with South Dakota State University

Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations

I grew up on dirt roads. This sounds like a cliché country song, but I did. The roads can get very bad in muddy conditions. I remember sliding around, sometimes going dangerously near and into the ditch, and even having to redirect our routes through pastures due to wash-outs. I remember having to miss events due to bad roads and this feeling unfair to me.

Although there is a sort of romanticism associated with dirt roads, I do not want to live on one again unless it is very short and at least gravel. I’m just not as backwoodsy as the rest of my family, I guess! I have four siblings and three of the four have moved back to the country, live near my parents, and engage in some sort of ranching. As for me? I like nice roads. I like sidewalks.

Although there is an environmental cost, paved roads and sidewalks represent progress to me. You can bike on them, run, skateboard, whatever you want to do. However, those dirt roads helped define me. I would walk those quiet roads, picking sticky sunflowers and tossing petals onto the ground, contemplating decisions, thinking about who I wanted to be. I rode with my friend Lydia on her go-cart on those roads, feeling a bit scared but exhilarated. We’d drive to an abandoned farm place and look around, wondering who had lived there and what they left behind. My siblings and I would walk up to our neighbors’ house and they would give us popsicles, pull out our loose teeth (at our request), and loan us books to read. I learned to drive on those roads, went on my first date, my first everything.

Another big factor in my story of self was growing up on a Reservation as a non-tribal member. Many people seem confused by this, but most of our neighbors were white ranchers and certain parts of the Reservation are like that. Later, in college, I learned it is called “checkerboarding.” The General Allotment Act/Dawes Act of 1887 attempted to encourage tribal members to become farmers. This did not always work out and some of this land was sold or transferred to non-Indian parties but remained within Reservation boundaries. A “checkerboard” pattern resulted, in which trust lands, fee/lease lands, lands owned by tribes, individual tribal members, and non-Indians are mixed together. Checkerboarding complicates tribal sovereignty: “Checkerboarding seriously impairs the ability of Indian nations or individual Indians to use land to their own advantage for farming, ranching, or other economic activities that require large, contiguous sections of land. It also hampers access to lands that the tribe owns and uses in traditional ways.” It also creates jurisdictional challenges.

Growing up on a Reservation, I saw people walking on roadsides (often with cars zipping by at 65 mph) and I wondered about their stories. I felt a pull to help, but I did not usually stop. One summer day I was driving home, it was nearly 100 degrees and I saw a man passed out in the ditch. My younger brother was with me and his eyes got really big and he said, “Let’s just keep going.” I said no. I picked him up, recognized him as our neighbor, and took him home. I thought about how unsafe this situation had been for our neighbor. It was so hot and exposed, he was probably suffering from dehydration, and a car might not have saw him. I worry about all of our relatives walking on roadsides, all over our state.

I see people run out in front of cars instead of using crosswalks. I know people in Rapid City that have been hit by cars on their bikes. I dislike how it seems like cars are kings of the road and the everyday mentality feels like cars vs. pedestrians/bikers. I have felt this way too, as I’m more often a motorist than a pedestrian/biker. I feel impatient when there is a biker ahead of me, pedaling as fast as they can, and I have to wait to pass them. I feel unsettled by the panhandlers at our interstate exits with their cardboard signs, “disrupting” my commute and my own selfish thoughts.

A month ago or so, I stopped at a stop sign in our neighborhood and saw a child zip in front of me on their bike, nearly out of control going down a steep hill. My heart started beating fast and then came the sibling/friend, barreling down the hill after the first child. I was so glad I fully stopped, as sometimes I honestly do not. “I totally paused,” as they say on Clueless, a 90’s movie.

Mostly, I just believe all people have the right to walk and bike places safely, whether it is by choice or not. I don’t believe many of our communities are currently set up to allow for this or that many South Dakotans share this belief. This, to me, is what needs to change.

Chrissy Meyer

Regional Communications Director; American Heart Association

Sioux Falls

2012 was the hardest year of my life. I was going through a divorce after 14 years of marriage, and I found myself on my own for the first time in my life.

I wasn’t destitute by any means – I had a good job and could provide for myself – but it was a significant change in my lifestyle. At that time (as now), I worked from my home, and most days I was there in my tiny new one-bedroom apartment alone.

By the end of the day, I had to break out of those four walls, so walking became my one form of mental (and physical) refuge. I looked forward to that 5-mile release every day. It helped me process a lot of emotions and helped me become the healthiest I’d ever been to that point in my life. Looking back, it really was those daily walks that made the difference for me.

Over time, I was able to build a new life. I saved and bought a house across town in a new zip code. I had enough disposable income to join a gym and continue my physical fitness. Life was good. And then… well… 2020 happened.

With the start of the pandemic, gyms were closed, so I – once again – took refuge in walking. But what I found was eye-opening. In my new zip code across town, the walking conditions were drastically different. I could walk south from my home and have beautiful bike trails and plenty of safe, welcoming sidewalks with grassy boulevards and trees, but if I walked north, the conditions were appallingly different. There I saw sidewalks directly adjacent to 4 lane roads with speeding traffic and streets with no sidewalks at all.

Around the same time, I started learning more about the social determinants of health and how they impact my community. In a nutshell, your zip code is a more important predictor of how long and how well you will live than your genetic code. I certainly was seeing that in my move across town. Could simply changing from a 57108 zip code to a 57106 zip code mean that my life could be shorter? How unfair. I want to make something change, not only for myself, but for my neighbors.