They fought a freeway and built a movement

By Hanna Brooks Olsen

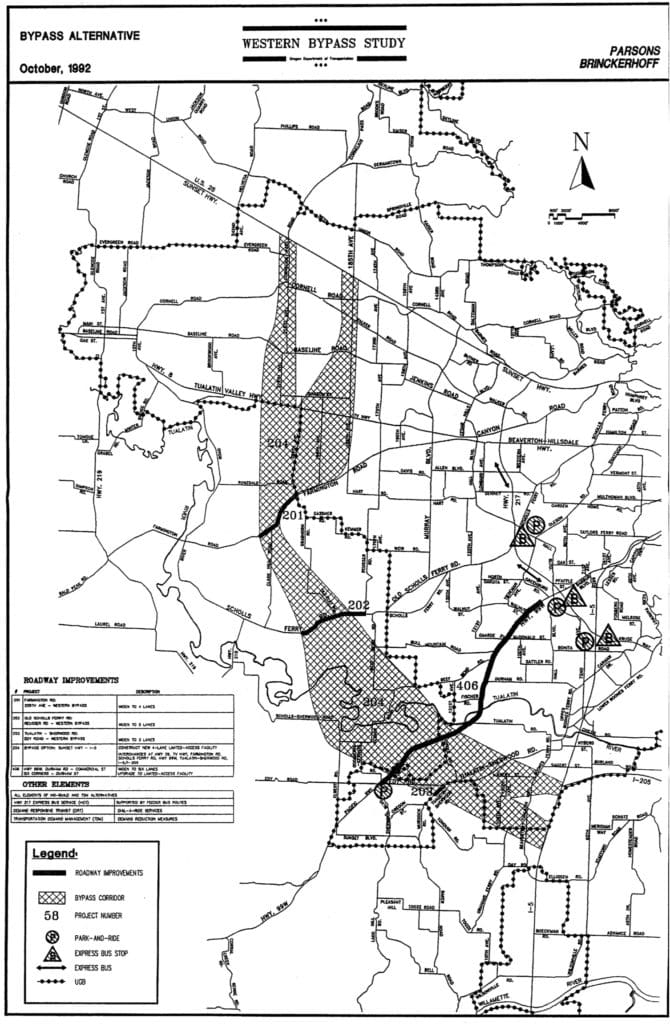

A quiet battle had been raging in Portland, Oregon, for a decade. In a plot to try to protect the state from the perceived “Californication” that came with unchecked sprawl and cloverleaf freeways, lawmakers created and passed innovative land use laws designed to protect farmland, create equitable housing opportunities, and temper the spread of suburban sprawl. But these new laws were open to wide interpretation — a battle that came to a head in the 1980s over a stretch of proposed freeway known as the Western Bypass.

For years, lawmakers and transportation advisors had been eyeing the burgeoning area southwest of Portland. What had once been almost exclusively agricultural land was being developed, creating bedroom communities for the big city — and putting a lot more people in their cars. The relatively-new I-5 freeway was doing its job, but there was still significant inner-city gridlock from motorists coming down from Washington into the Willamette Valley. The de rigeur solution? Build another freeway. Well, technically, a beltline; the kind of road that lets drivers speed through suburban areas on their way to and from the city.

It would be called the Western Bypass. But it was not to be.

Residents were first made aware of the plans not through dispatched from the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) or local government agencies. Instead, the news broke in The Oregonian as part of a larger story about proposed roadway expansions and construction. Activists started coming to meetings to find out what, specifically, was in the play. When they finally learned more, their concerns were confirmed.

“The proposal for the freeway didn’t justify the freeway,” said Molly O’Reilly, one of the organizers of Sensible Transportation Options for People (STOP). O’Reilly told America Walks’ Ian Thomas about the experience in a recent interview. It would create more sprawl, she said, not less. And it didn’t match with the State’s still-fresh growth rules.

So STOP hit the streets, “giving presentations and sowing discontent,” O’Reilly explained.

“We…coordinated with a lot of other people to get behind-the-scenes support. So we had to tick off support, and we managed to do that, but then we had to also make it possible for [the impacted municipalities] to object.” Unfortunately, with ODOT backing the plan, “no one wanted to step out in front.” Local advocates like O’Reilly knew they would need data and information to back up their opposition. They reached out to land use and planning group 1,000 Friends of Oregon, requesting a survey. They wanted to know “what would happen if you didn’t build the freeway, but instead, you had really good transit and smart land use.”

This survey, called the LUTRAQ (Land Use, Transportation, and Air Quality) project, created a new rubric for freeway proposals, capital projects, and smart growth strategies.

LUTRAQ

In a 1997 report about LUTRAQ, 1,000 Friends of Oregon detailed its purpose and what set this project apart from the standard surveys and data collection:

By challenging conventional assumptions, the LUTRAQ project charted new territory in land-use and transportation planning. LUTRAQ did not accept the assumptions that providing mobility to a growing population required highways on an ever larger scale, that alternative modes would never provide significant relief from the need for auto trips, or that the number and length of trips could not be reduced by changes in land-use and other policies.

Instead, LUTRAQ presented new assumptions that were tested by careful analysis of market and demographic trends. The result was the LUTRAQ alternative, a different plan for land use and transportation that was added to ODOT’s environmental impact statement process for the Western Bypass and, ultimately, adopted as part of the region’s vision for the future.

“They had real credibility when they were done,” O’Reilly remembered.

When the State of Oregon rolled out its new land use guidelines and growth management rules, many of the specifics had yet to be ironed out. Additionally, the changes didn’t always roll downhill, meaning local officials were studying areas (like farmlands where they might put freeways) without new, comprehensive guidelines to match the rules.

LUTRAQ brought with it the kinds of design strategies that we now embrace today, like transit-oriented development (TOD). Instead of using the same approaches — highways — to meet new goals, lawmakers and transportation authorities would have to come up with different plans and different modeling as well.

Again, from the report:

The analysis showed that, at the end of 20 years, the LUTRAQ alternative had the potential to be superior to the “Highways Only” option on all key criteria used in the evaluation:

- 22.5 percent fewer work trips made in single-occupant vehicles

- 27 percent more trips made on transit and by walking and biking

- 18 percent less highway congestion with 10.7 percent fewer hours of vehicle travel during the afternoon rush hour

Numbers like this — as well as the innovative approach to urban planning and land use surveying — were hard to fight. And as the 1980s gave way to the 90s, environmental activism in Oregon flourished. Support for the project continued to wane as advocates presented more and more alternatives, like rapid transit and walkable community construction.

Eventually, the plan was quietly axed from the State’s broader transportation future. And while the Western Bypass is a faint memory for those who fought against it, its ghost still haunts the region. Aspects of the Bypass — like an additional bridge spanning the Columbia River — remain open questions.

“The third crossing is still an issue,” O’Reilly explained. “People who know transportation know that you’ve got to build it right next to your old bridge…otherwise you just create more traffic than you resolve. Anything you build, you’ll fill.”

The battle over the Western Bypass may not have ended Portland’s freeway fights for good — there are still activists across the Rose City who are creating and presenting better, more walkable futures — but it did create a new tool to help these current advocates continue the important work started long before they were born.