Recently, Ari Faruk, Policy Director of Families Forward Virginia, tweeted about his local library. The newly-remodeled library includes computer workstations outfitted with small, enclosed areas for folks who are caring for young children. It’s a brilliant feature that can open up new worlds for a harried caregiver. But as another Twitter user pointed out, the library’s family-friendly design ends at the front door.

It isn’t reflected in the infrastructure surrounding it.

Family-Friendly Design Shouldn’t Stop At The Property Line

Schools, libraries, community centers, and public parks are necessary investments. They ensure that individuals of all ages can work, live, and get the most out of their neighborhoods. We need services and spaces designed specifically for the needs of families, seniors, young people, and new Americans.

But why do areas like Richmond , Virginia, invest in gorgeous new libraries — with smart, beautiful elements on the inside of the building — while failing to also address the lack family-friendly design outside?

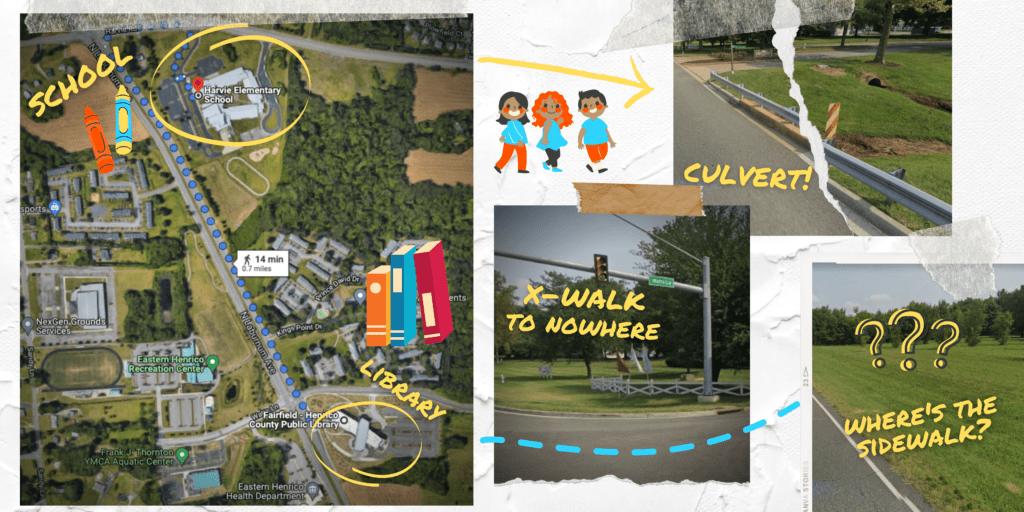

This library is a great example of the failure to plan beyond the property line. Less than a mile from an elementary school, the library is theoretically sited for use by families. But looking closer at the reality of the location, it’s isolated. It’s all but impossible for children to walk from the school to the library safely. Incomplete sidewalks, a ditch, and safe-moving vehicles all put kids at risk.

Additionally, the library is across the street from a YMCA. This should be optimal — the Y is a reliable source of after-school care in many communities. Instead, it’s a hazard, because getting to the other side of this busy street is nearly impossible.

It’s not uncommon. Large capital investments are frequently built in a design vacuum. They’re funded and planned on their own, without regard for the travel or traffic patterns that might lead people to the spaces.

Which forces an important question for urban planners, elected officials, and backers: If a library exists on a busy road with limited bus service and no feasible, safe walking routes, is it really fulfilling its intended purpose?

Building for How People Move

This problem isn’t new — and it’s not a secret. Sometimes, it’s not even accidental. Back in 2014, one middle school in Sioux Falls was specifically constructed without sidewalks to discourage students from nearby neighborhoods from walking. And while that’s an extreme example, it’s also an important illustration of the backwards approach many administrators are taking to urban planning. Too frequently, the planning begins and ends with the building itself. Instead, planners should work to build a comprehensive map with routes that take people from door to door.

Organizations like Vision Zero For Youth have been working to bring attention to the specific intersection of traffic violence and a lack of family-friendly design in cities and towns. By encouraging “communities and elected officials to focus on safety improvements and efforts to slow traffic speeds where children and youth travel,” Vision Zero For Youth has worked with lawmakers and community leaders to plan for safe routes to family-focused locations. From their site:

Starting safety initiatives near schools and in areas where youth often walk and bike, first and foremost creates a safer environment for children. In addition, prioritizing the needs of child pedestrians and bicyclists can form an integral piece of a plan to meet larger safety goals. Safety measures targeted at protecting youth, whether in controlling speed, creating safer, improved walking and biking facilities, or in changing behaviors, have broader effects that benefit entire communities.

Vision Zero for Youth has been successful across the country. They’ve helped to create road diets on busy arterials close to schools and added flashing pedestrian sides, crosswalks, and bike lanes near commuter train stations and bus stops.

And Of Course, People Like It

The City of Missoula took on the fight for wider sidewalks around a new library in 2018 — and won. This victory was largely because the councilmembers voting for the project realized that people would enjoy a large, landscaped barrier between the street and the building.

During the discussion, Councilmember Gwen Jones remarked that “it’s aesthetically beautiful. It’s a much better walking experience.”

“People will continue to live in this neighborhood for many, many decades,” she explained. Jones added that the wider sidewalks, which required a vacation for a city-owned right of way, would provide “a much better walking experience and will be far more inviting.”

Which is ultimately the main goal for most lawmakers — to design something that people like and use. And, as Ari Faruk’s viral tweet about the family-friendly design of the library workstations demonstrates, people really do like it when their tax dollars are used for something thoughtful, meaningful, useful, and beautiful.

This example also highlights the need to site schools and libraries near similar, existing services. In a 2018 report, Safe Routes wrote that the “built environment factors that promote active school commutes (i.e., proximity to public transport, walkability) should be considered when making decisions about school siting.”

Siting, though, clearly isn’t enough. Though the library in question is geographically near a community center and an elementary school, it’s impossible for users to safely get from one to the next. On paper, this library might look perfect sited — it’s close to transit and other services. But without the construction of additional paths, sidewalks, crosswalks, curbs, and traffic calming, city planners have essentially built a beautiful library on an island.

Like, say, wide boulevard sidewalks near the new library. Or a traffic calming device on the busy four-way street. Or a bus that comes more than once per hour.