America Walks leads the way in advancing safe, equitable, accessible, and enjoyable places to walk and move by giving people and communities the resources to effectively advocate for change. We know that meaningful, catalytic change starts at the grassroots level, which is why we put a lot of thought and care into selecting the America Walks Community Change Grantees. This year we awarded 18 awards to different communities across the U.S. to support unique walkability projects. Here is a glimpse at some of the highlights of the program and what local walking champions are up to at the ground level.

LEARN MORE / APPLY NOW FOR A 2021 COMMUNITY CHANGE GRANT!

The Jackson Medical Mall Takes Walkability in a Whole New Direction

It’s been a noticeable trend for years –– people like to walk at the Jackson Medical Mall (JMM) in Jackson, Mississippi. The JMM is like a destination for movement, especially for older populations and for those who live in the nearby areas where sidewalks are not safe, accessible, or well-maintained. Whether they be patients, visitors, staff, or community members looking for a meal or products from vendors, the JMM is a safe haven for daily physical activity because it is secure, relaxed, enjoyable, walkable, and temperature appropriate.

Thousands of people visit the mall daily, with more than half visiting for medical care. There is a walking trail but it’s utilized by less than 1% of patrons per day. The Jackson State University School of Public Health, (em) Power Walking Program noticed the potential to use the trail and get people walking. The solution? Creating encouraging signage to get folks moving more.

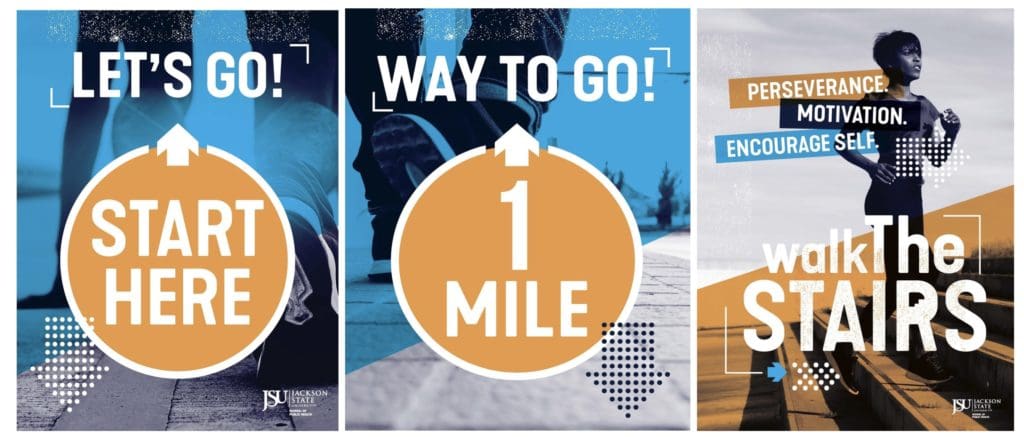

A few of the vibrant, encouraging mile-markers and signage to promote more walking and physical activity through The Jackson State University School of Public Health, (em) Power Walking Program.

The program has featured various activities like installing mile markers along the mall perimeter and signage to encourage the use of stairs. They also host 15-minute speaking sessions to empower the community and disseminate educational information on the benefits of walking.

Yalanda M. Barner, Director of Marketing/Field Placement at Jackson State University’s School of Public Health, says thriving partnerships with the Mississippi State Department of Health’s Move Your Way Campaign and the Jackson Medical Mall Foundation have been critical in securing influential speakers and getting people motivated to move. But there is another factor she finds crucial.

“We can’t ask somebody to do something we’re not doing. So we’re always out there walking as well. We have quite a few faculty and staff members who go out in the medical mall and walk. We try to lead by example. I think that’s the only way,” says Yalanda.

The (em) Power Walking Program will assign students to observe, track, and monitor any increases in moving and walking post mile markers, to get a sense of the impact these have had on patrons. They also plan on spreading flyers and working on the grassroots word of mouth outreach to get other vulnerable or underserved community members to walk at the JMM.

Shinnecock Indian Nation Prioritizes Connections to People-First Infrastructure

Every life lost while walking is a tragedy. But Lauryn Randall, Church St. Crosswalk Project and Transportation Coordinator at Shinnecock Indian Nation, in Long Island, New York, says there is a particular kind of trauma that haunts tribal communities when crashes injure or take the lives of family and friends in a community as related, tight-knit, and historically underserved as the Shinnecock Indian Nation. This narrative is a piece of the backdrop that informs Lauryn’s people-first work and what ended up nudging her and a colleague to apply for and receive the America Walks Community Change Grant.

Nestled in the middle of the Shinnecock Indian Reservation is an array of buildings that provide essential health, social, and educational services to the community. However, Church Street, where they all intersect and connect, has a dangerous blind curve that makes it unsafe and challenging to cross. In fact, people will often drive to and from these buildings that are right across the street from one another just to be safe but ignoring an important opportunity for physical activity.

“People come around that curve pretty fast and the vegetation has overgrown so it’s literally a blind curve… no sidewalks, no parking lots, no shoulders, very narrow, it doesn’t take into account people walking, biking, on scooters, etc.,” says Lauryn.

After consulting with engineers from the tribal transportation technical assistance program, traffic planners, and other community liaison folks, the tribe established a goal to create a safe zone with fun crosswalks and walkways that encourage walking from building to building and allow children to safely access the nearby playground and basketball court.

The Church St. Crosswalk Project is part of a larger movement toward safety and people-first design and infrastructure on the Shinnecock reservation. This America Walks Community Change Grant is the first set of grant funds to support this work on the reservation. The implementation process will include installing signage and speed bumps to significantly reduce traffic speed, pushing back overgrown vegetation to create a grass sidewalk, and painting crosswalks with culturally relevant designs.

“When you show people where to go, like they can see the path to the crosswalk, they’re more inclined to use it,” says Lauryn.

The work starts this summer with a tactical urbanism pop-up to mark up the crosswalk path. Kids attending the Shinnecock Cultural Camp will be assisting and learning with some traffic safety education outreach, thanks to key partners like The Shinnecock Health Clinic Administrator, Western Suffolk BOCES School Coordinator for Creating Healthy Schools and Communities (CHSC), and Stony Brook Universities CHSC Coordinator, as well as Cornell Cooperative Extension’s Nutritionist.

Living Cully Walking Group Takes Grassroots Community Action to New Heights

Verde, based in Portland, Oregon, led the development of Cully Park, a 25-acre park built on a former landfill that opened in 2018. While Cully Park was still under construction, neighbors identified the need for a community led walking group. The rest is a story that highlights a commitment to equity, inclusiveness, and physical activity. The group has three women Latina leaders and about 15 walkers who all identify as low income and Latinx.

The Cully neighborhood has a lack of active transportation infrastructure –– only 34% of the streets have sidewalks, there are busy highways between the residential areas, and some of the green spaces are along an industrial corridor. Verde works to eradicate these barriers.

The America Walks Community Change Grant has helped facilitate five neighborhood walks, connecting community members to exercise opportunities and a safe way to get to Cully Park. The walking group leaders, led by group leader Malin Jimenez, also completed neighborhood clean-ups during their twice monthly walks, picking up trash, reporting illegal dumping and graffiti, and keeping the area safe and clean. The leaders all receive professional neighborhood watch training through the City of Portland’s office of civic engagement.

“When we first started we were only going to Cully Park and now we’re able to expand to other areas of the community. An empty Habitat for Humanity lot reached out to us to patrol, report, and help keep it clean. The community seems really excited to partner with other organizations and support the group as well,” says Malin.

Malin recently facilitated another partnership with a nearby Latina health clinic who advocates for access to the Columbia Slough natural area and possible trails, and patrols Living Cully Plaza too.

Anna Gordon, Verde’s Community Programs Manager, says they want to ensure the right people are always at the table making decisions.

“Whether it’s be able to attend a community meeting where we can provide childcare, translation or meals, or providing an opportunity for leaders to consistently lead walks in the community –– when we’re able to provide stipends or resources it makes it possible for low-income community members to participate. When otherwise they may need to be working or caring for the kids, those things that everyone has to do in their busy lives,” says Anna.

She says this model has paid off massively, as members from the group now speak at a number of active transportation events and present to regional government and other agencies, functioning as spokespeople for the work they do.

“Opportunities like the walking group give community members a sense of pride and ownership of community projects. They are the caretakers of these spaces and that is really powerful in terms of building community.”

Walk With Ease Inspires Pain Reduction and Boosts Social Connections

The barriers to exercise are well-researched and real –– people report being too busy, they lack the time or energy, or simply can’t get motivated. With chronic pain it can be even more difficult to find the motivation to walk and move. The Arthritis Foundation Walk with Ease Program in Portage County, Wisconsin aims to break down those difficulties in hopes of empowering older individuals to understand why walking is medicine and how best to make it a habit.

Walk with Ease is a six-week workshop and walking program that fosters a healthy and safe walking routine for people with arthritis, but anyone who has mobility issues or is sedentary is welcome to join. Volunteer leaders will meet with participants in areas with walking trails and indoor facilities to build friendships and endurance. Health literacy with health educators and reducing social isolation are also big components of the program.

Kate Giblin, Health Promotion Coordinator for the Aging & Disability Resource Center of Portage County Lincoln Center, says that through public surveys they’ve discovered that the very people they want to serve can still have a deep reluctance to stepping out into a public place due to feeling uncomfortable.

“So people acknowledge and appreciate that this is a peer group and creates a

cohort of people who are all in the same boat. I think that’s what’s attractive about the program. It should facilitate a reduction of social isolation and a much more welcoming atmosphere,” says Kate.

She has connected a coalition of groups together, like counseling facilities and health and wellness departments, through unique partnership cultivation. Kate says future goals for the program are to offer it multiple times per year, in rural communities as well.

“I’d like to use the program as an ambassador to continue to partner with different community organizations like our school, the local youth club, churches, and others, to try to not only get everyone walking but to create that intergenerational and family experience.”