On Tuesday, April 29, 2025, fifty advocates and professionals gathered in Pueblo of Jemez, New Mexico, for a tribal pedestrian safety workshop and quick-build demonstration.

This event — part of a Road to Zero grant-funded project titled “Pedestrian Fatalities in Indian Country: Responding to a Crisis” — attracted activists, tribal leaders, planners, engineers, public health experts, state and federal government officials, consultants, and researchers from around the country. Six tribes (Pueblo of Jemez, Pueblo of Zia, Navajo Nation, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes) and three State Departments of Transportation (New Mexico, Washington, Alaska) were represented.

The event focused on curbing a public safety epidemic, which has received very little attention. American Indians and Alaska Natives are killed while walking along and across public roadways at a rate over three times higher than the national average (Smart Growth America). State highways cutting through tribal communities with so-called “forgiving” road designs, which encourage excessive vehicle speeds, are responsible for the high rates of pedestrian fatalities in Indian Country.

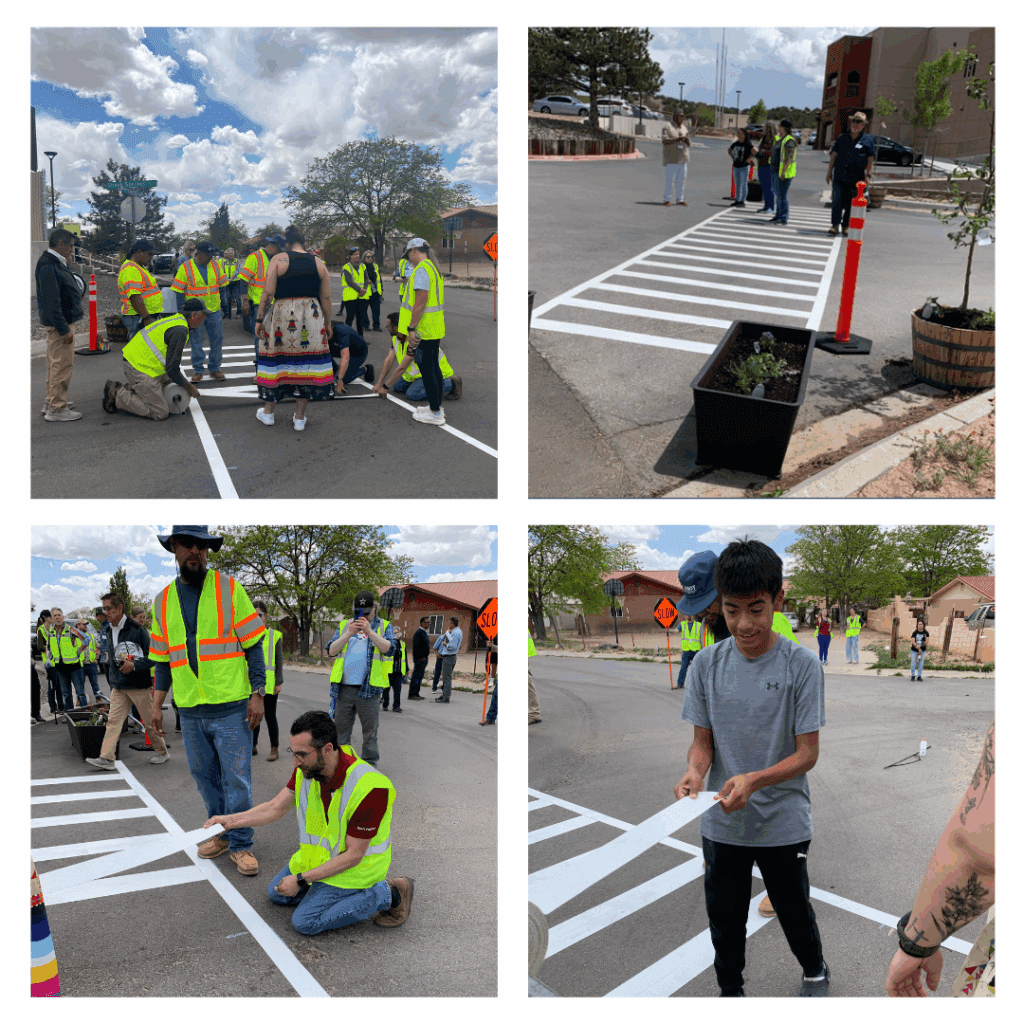

During the workshop, members of the Road to Zero project team gave presentations and facilitated group discussions on speed management strategies. Afterwards, participants went outside to install a “quick-build” traffic calming project. They were joined by local residents (including several children) for a community-based activity through which the people who live, work, and play in that neighborhood helped re-imagine and re-design their built environment.

The most labor-intensive task was the striping of two “ladder crosswalks” using pavement tape.

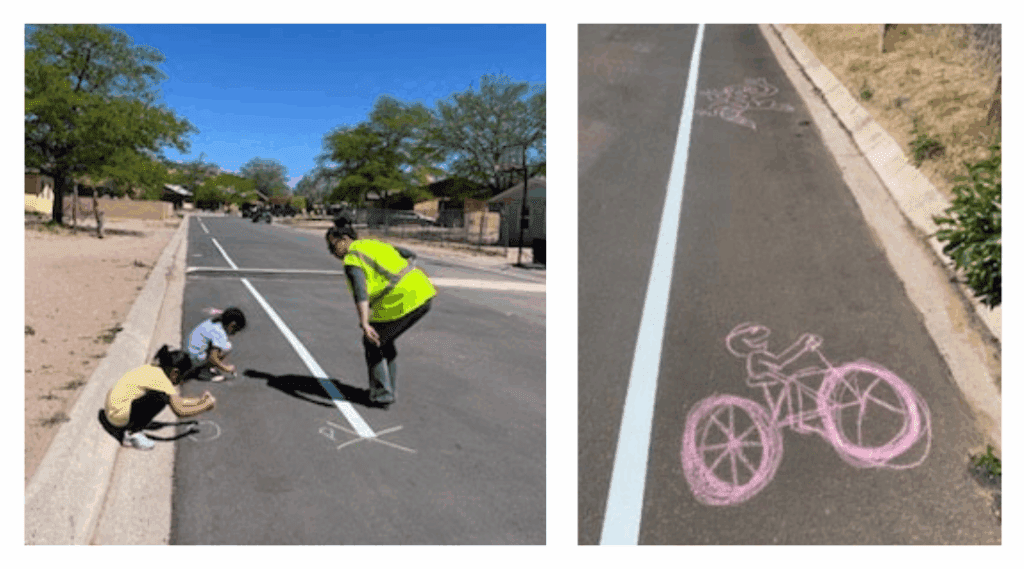

While the crosswalks were being striped, another crew installed a protected walking path.

And quick-build “aesthetics” were provided by planters and sidewalk chalk art.

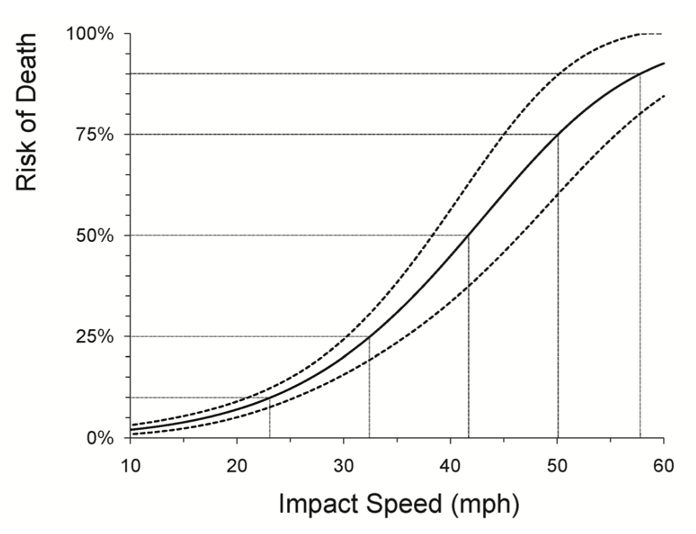

The goal of the quick-build traffic calming project was to reduce vehicle speeds so that collisions with pedestrians would be less likely and (if they do happen) less severe.

If a car traveling at 60 miles per hour strikes a pedestrian, there is more than a 90% chance that it will be a fatal crash (AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety). However, if the vehicle’s speed is reduced to 50 mph, the fatality risk falls to 75%. At 40 mph, the pedestrian has more than a 50:50 chance of surviving. At 30 mph, the probability of death falls to about 20%, and at 20 mph it is less than 10%. To address high pedestrian fatality rates, vehicle speeds in the areas where people live, work, and play need to be reduced to 30 mph — preferably 20 mph.

One approach to achieve this is to reduce speed limits. However, “safe systems” research by the State Smart Transportation Initiative reveals that most motorists do not make intentional decisions about how fast to drive. Instead, visual cues from the roadway ahead directly influence the drivers’ operation of the accelerator pedal, effectively bypassing the conscious brain. Wide travel lanes going straight ahead with large open spaces alongside the roadway induce high vehicle speeds irrespective of the posted speed limit. Basically, drivers adopt the speed dictated to them by the design of the road. While these high speeds may be safe on a separated highway with off- and on-ramps, they are deadly in more complex environments, which can include driveways, turning vehicles, and vulnerable road users.

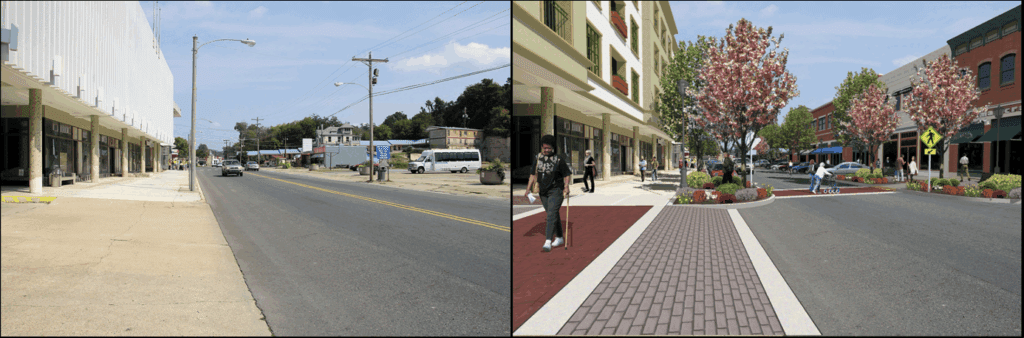

Conversely, narrow lanes, limited sight lines due to street curvature, and the proximity of landscaping, buildings, and parking next to the travel-way naturally induce slower, safer speeds. The concept of “visual friction” refers to the sense of a rough edge to the road which makes drivers slow down. This effect can be created by trees, pedestrian bulb-outs, and parked cars.

Dan Burden developed the following graphical visualization to show how to reduce driving speeds by changing road design parameters and adding streetscape elements. Even though the roadway corridor depicted in these two images is the same, motorists would drive slower and more cautiously along the street on the right.

This transformation from a high-speed, car-oriented road to a safe, inclusive, multimodal street would involve a long, expensive planning, approval, design, and construction process. However, a temporary quick-build project can achieve a similar visual impact, and thereby reduce vehicle speeds, by using inexpensive materials such as landscaping planters, plastic delineator posts, and pavement paint.

As demonstrated in Pueblo of Jemez, quick-builds can be community-led initiatives in which residents, business owners, and even schoolchildren design and install a demonstration project with the guidance of consultants. By announcing in advance that a particular quick-build is an experiment that will only remain in place for a few weeks or months, advocates are often able to blunt opposition that would “kill” a permanent project. During that temporary installation period, speed studies and surveys may be conducted, which invariably show safety benefits and community approval. In many cases, a temporary quick-build leads to strong public support and the political will necessary to approve and fund a permanent project.

This theory of change — using quick-builds to smooth the path for permanent traffic calming solutions — has not been widely attempted in tribal communities, where excessive speeds and pedestrian fatalities are common. The Pueblo of Jemez project is a pioneering example. Community feedback has been very positive, the crosswalks and walkway are in regular use and good condition, and the Jemez Department of Transportation has decided to leave the installation in place for the foreseeable future, even though the original plan was to remove it after four months.