In many parts of the country, the most beloved neighborhoods are those that keep late hours. Street cafes with twinkling string lights. Festive displays during the holiday season. Well-lit corners with ample visibility for folks crossing the street. Many residents want more street lighting in their area to create a greater sense of safety at night.

But our ability to light the way has also become a problem. The darkness of night isn’t passive or neutral — it’s essential for the flora and fauna, including humans. Light pollution threatens trees, animals, and human health. According to the International Dark-Sky Association, light pollution impacts everyone.

Which creates a potential source of stress when advocating for equity, walkability, climate protections, and safety. Is there a way to meet the needs of both folks on the street and the planet?

Of course there is. We just have to acknowledge where the friction may be and address it one step at a time. Which requires a recognition that two things can be true. First, that street lighting makes people feel safer, and thus, encourages more foot traffic. Second, hat street lighting has historically been a source of problematic nighttime brightness. However, with modern innovations in lighting — and active input from pedestrians, cyclists, and others who want increased visibility on the streets — it is possible to marry these two very real needs. We can create streets that feel safe without washing out the night sky with artificial lighting.

Addressing Light Pollution Through Policy

Light pollution comes from any number of sources, including billboards, tall buildings, large-scale signs, sports stadia, and many more. The light can reflect off of bodies of water, windows, clouds, or even wet streets. This light amplifies itself, creating an echo effect. The lack of a “true night” can upset the natural functions of plants, people, and other animals.

Or, as the International Dark-Sky Association:

“..Artificial lights overpower the darkness and our cities glow at night, disrupting the natural day-night pattern and shifting the delicate balance of our environment.”

The awareness about light pollution has increased significantly in the last two decades. This has lead many cities and states to adopt their own Dark Sky policies. In fact, in 2021, Flagstaff celebrated the 20th anniversary of becoming the first Dark Sky city in the United States. The city’s efforts have included the creation of strict zoning standards around nighttime lighting and finding ways to reduce excessive lighting in the commercial and recreational industries.

In a 2018 report, Flagstaff’s government even noted that “the concerns of safety, utility, dark sky protection and aesthetic appearance need not compete.”

“Good modern lighting practices can provide adequate light for safety and utility without excessive glare or light pollution. Careful attention to when, where, and how much night-time lighting is needed results in better lighting practices, darker skies and reduced energy use and costs.”

Unfortunately, not all cities have paid attention to that piece of the puzzle.

The Fight Over Street Lighting

When looking for sources of light pollution, street lighting is an easy target. But, as the City of Flagstaff found, they aren’t the most significant by a long shot. Instead of removing street lights, Flagstaff worked to change other areas to balance health and safety.

Just like in almost every other area of infrastructure, cities have not equally distributed or maintained street lights. The Rice-Kinder Institute reported, in a 2017 article, that “predominantly white neighborhoods, on average, have lower concentrations of streetlights than black or Hispanic neighborhoods. The trend is …”consistent with a surveillance perspective regarding the placement of streetlights.””

Yes, really. Poorer neighborhoods, immigrant neighborhoods, and those with a high concentration of People of Color actually have more street lights. But removing those street lights isn’t going to fix all of the other infrastructure problems in those same neighborhoods; for some people, street lights are viewed as necessary for safety, while others feel that the excessive light is obtrusive.

That means, if you’re working within a framework of equity, you have to consider the role of streetlights, the kind of street lights, and how they’re going to be deployed. Specifically, it means being very discerning about the kinds of lights you’re providing and where. Because the fact is, a lot of people want lighting in their neighborhoods.

What Safety Lighting Means

Numerous chapters of the Dark Sky network have actively rallied against any new street lighting, citing that any new lighting will automatically add to light pollution. However, this doesn’t take into account the other ways in which we could be reducing excessive light or creating more functional light — ways which may have a much greater impact, both physically and socially.

Consider this: A street has a half-dozen restaurants on it, all of which have light-up signs which remain on, even after the close of business. Meanwhile, it has twice that number of street lights for safety, all of which provide a fraction of the output. Why not first limit the amount of advertising signs permitted to be on at night? How would that impact the neighborhood?

The City of Portland, Oregon noted in a 2020 report that while overhead street lighting can help increase feelings of safety, glaring lights do not.

“Light pollution, especially glare, also poses safety and security risks particularly relating to pedestrian and driver safety and comfort levels, and crime. Overly bright and poorly designed lighting contributes to glare.”

Which means that when we talk about lighting and, specifically, street lighting for pedestrians, we have to acknowledge that street lights vary. And because of this variation, lawmakers and planners need to make a concerted effort to get it right.

Creating Street Lighting That’s Safe and Smart

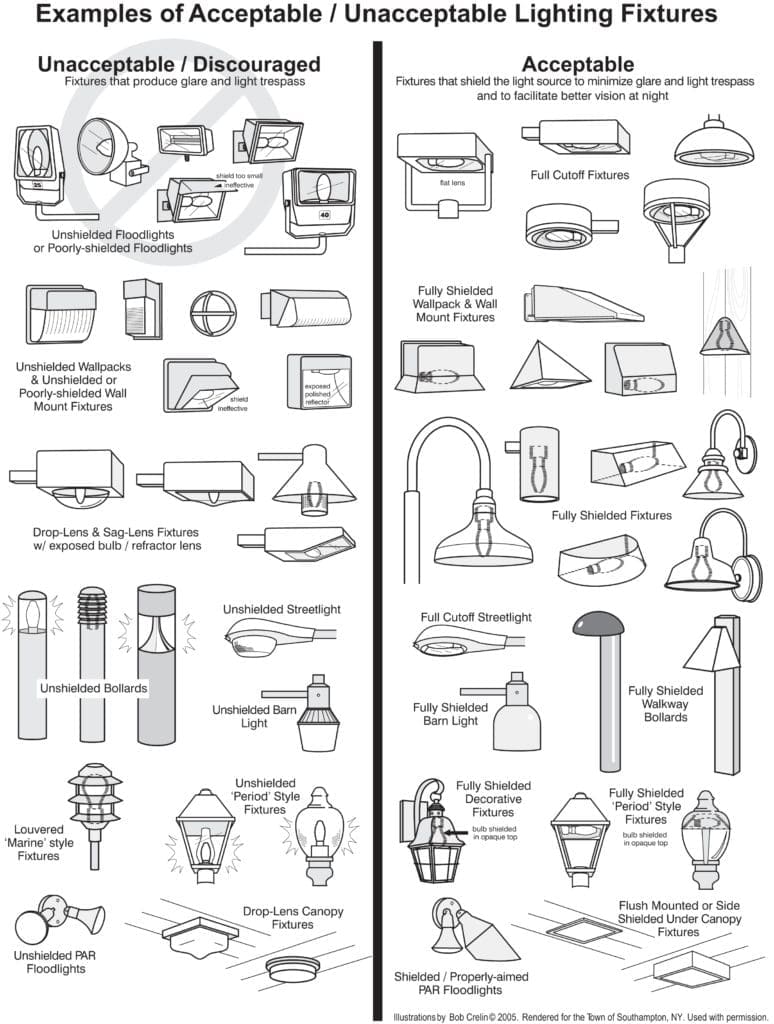

New options, like motion-sensored lights, fully-hooded street lights that keep light pointed down, and adjustable lights which allow areas to test which degree of lighting is most effective can all help cities reach these goals. However, this only happens when lawmakers know that they need to comparison shop, rather than just taking the most inexpensive bid that comes their way.

Ideally, street lighting should help people get around safety, reduce distraction and glare for motorists, and do as little damage to the environment as possible. And while that may seem like wishful thinking, it’s proven to be possible in some areas of the country. Pittsburgh, for example, made the news in 2021 for their broad-ranging Dark Sky initiative. In a report on the move, which was the product of years of lobbying by activists and advocates, Carnegie Mellon University noted that “the ordinance aims to improve safety and security, reduce light pollution, save energy and advance equity in all Pittsburgh neighborhoods.”

The report went on to state that “communities of color…experience over-lighting and light pollution — which can negatively impact mental and physical health — at a disproportionate rate.”

Striking A Balance

Not everyone is going to get it right. There are some cities which have renovated their street lighting for the express purpose of course-correcting to provide greater equity, increasing safety, and acknowledging light pollution. LED lights have gained popularity in the last several decades for a variety of reasons and, regardless of light pollution, cities have been making the switch. New LED lights can reduce energy costs, but may also be cooler in tone and brighter. In some areas, the new LEDs have made the problem of light pollution worse, not better. But many others have gotten them right. The key — like so many policies — is finding the right balance.

According to the Department of Energy, new LED systems “can be adjusted to provide only the level of illumination needed at any given time, and can also offer a high degree of control over the direction in which light is emitted.” This ability to control the lights and when or how they shine is essential and “makes it easier to reduce glare, light trespass (the spillover of light into areas where it’s not wanted), and uplight (which contributes to the phenomenon of “sky glow” that reduces visibility of stars in the night sky).”

Working Together

Some cities may not have taken into account the potential impact of a new or different kind of lighting. If you live in an area that’s over-lit, where the lights are too bright or too cool, you’ll likely be able to find support among others who want to see a change. That change doesn’t have to be dramatic, either. Steps to correct over-lighting may be as simple as turning down the brightness or minimizing blue light emissions. Cities can also install hooded fixtures or those which otherwise cast the light down, LEDs can absolutely strike a balance between lower energy costs and lower levels of sky glow.

The important piece of the conversation about light pollution vs. safety lighting is that is doesn’t need to be a fight at all. Focusing on pedestrian lighting may not be the most effective first step, but it is one that people care about. A city survey on commercial lighting, parking lot lights, and other unnecessary sources of nighttime lighting may reveal that reducing light pollution isn’t just about tearing down or replacing street lights. It may, instead, be about auditing the priorities of your city. You may be able to shed some light on how these decisions get made and who is getting the bulk of the consideration.