The same measures that we take to make cities more walkable can help fight urban heat and its impacts

Picture taking a walk along a beautiful street. Maybe you’re heading to get a cup of coffee or to meet a friend on a park bench. Huge, shady trees block the sun but allow enough dappled light to graze the sidewalk. Flowers and shrubs bloom, filling the clear air with soft fragrance. The occasional car passes by, but it goes slowly. This is what we think about when we think of walkability. And it’s also a list of ways that planners, city officials, neighbors, and developers could help fight the increasing threat of urban heat islands.

What Is An Urban Heat Island?

Even if you’ve heard the phrase “urban heat island,” you may still not understand what, specifically, it refers to. Here’s how the EPA defines it:

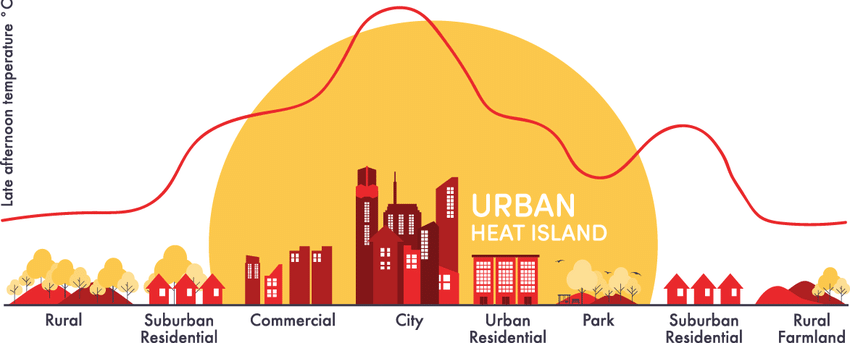

“Urban heat islands” occur when cities replace natural land cover with dense concentrations of pavement, buildings, and other surfaces that absorb and retain heat. This effect increases energy costs (e.g., for air conditioning), air pollution levels, and heat-related illness and mortality.

Dense new construction, paving for roads and parking lots, coupled with the removal of trees and other flora and idling vehicles all lead to increased emissions and trapped heat. Trapped heat means more people using their air conditioning, which then releases even more emissions.

Why Do Urban Heat Islands Matter?

It’s not just a matter of a few degrees. The increased heat can quickly become untenable for plants and animals — including critters outside of the urban core can be impacted. A report from this year found that forest birds, too, suffer greatly from urban heat increases.

And of course, like pretty much every element of climate change, it disproportionately harms humans who are already living on the margins. Poorer areas, traditionally Black and brown neighborhoods, and areas with a lot of seniors have all been found to experience even hotter temperatures. In some cities, this has even led to fatalities.

Additionally, urban heat islands have a cyclical impact. The hotter it is, the fewer people walk — and the more they drive, run their air conditioning, and generally release more emissions into the air. Urban heat islands are both an effect of climate change and a cause.

But it’s not unfixable. We know what to do — and it’s most of the same things we’re trying to do to make cities more walkable, too.

Walkability: Good For Turning Down The Heat

Some of the suggestions to help reduce heat in cities are the exact suggestions that make our streets more pleasant for people walking and rolling. The exact attributes we all love while on foot or using a mobility device — greenery, fewer large slabs of concrete, more shade, and smartly-built homes and businesses — can help reduce the temperature in cities and towns.

The EPA suggests building new construction with green roofs and including ample foliage. Some cities are also backfilling and recreating their tree canopies by reclaiming land from parking lots, mini-malls, and other development that increases the heat. Planting trees on islands, in parking strips and lots, and as part of landscaping is also a way to increase shade, add greenery, and trap carbon emissions.

Specifically, these should be “native, drought-tolerant shade trees and smaller plants such as shrubs, grasses, and groundcover wherever possible.” Bioswales and other methods of groundwater protection are also important for the trees (and the people) in a region.

From the brutalism of the 1950s and 60s to the massive commercialism of the 1980s and 90s, many of our design and development trends have gone out of fashion — both stylistically and with regard to protecting our people and our planet. To curb urban heat islands, we need to design for user experience.

Learn more about climate and how it relates to walkability and other sectors like transportation at our upcoming webinar happening July 27th at 2pm ET. Register today.