When you think of walkability, do you imagine an urban streetscape? The reality is that rural communities designed around a main street with local shops, services, housing, and institutions for civic life provide gathering spaces that make them ideal candidates for walkability.

During a recent webinar on the topic, guests Shane Hampton, Senior Manager for Thriving Communities at Main Street America; Stefanie Mitchell, Council Member for the Town of Westville, Oklahoma; and Amy Miller, Program Officer for Main Street America, shared stories of how rural communities across the United States are prioritizing walkability as they improve their main streets and downtown areas.

The webinar was made possible by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Active People, Healthy Nation campaign, which is aimed at increasing physical activity and improving health and quality of life.

Shane began by introducing Main Street America, which leads a movement committed to strengthening communities through preservation-based economic development in older and historic downtowns and neighborhood commercial districts. Main Street America also worked with 20 communities — focused on Tribal, rural, and small-town communities — through the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Thriving Communities program to approach their own transportation challenges.

Rural communities face unique challenges, but they are more compatible with walkability than you might think. “Many rural places are set up with the bones to support walkability,” said Shane, and interventions to make communities more walkable have positive effects on health, safety, accessibility, economics (including tourism), social ties, and overall quality of life.

Stefanie, a lifelong resident of Westville, Oklahoma, turned volunteer Council Member, spoke about the effort to revitalize her small town of 1,600 people and break the cycle of persistent generational poverty by investing in the built environment. The breakthrough win for Westville — the “spark that lit the fire,” according to Stefanie — came in the form of a splash pad in downtown, which led to the building of a pavilion and better lighting along the nearby walking trail, as well as improved public bathrooms.

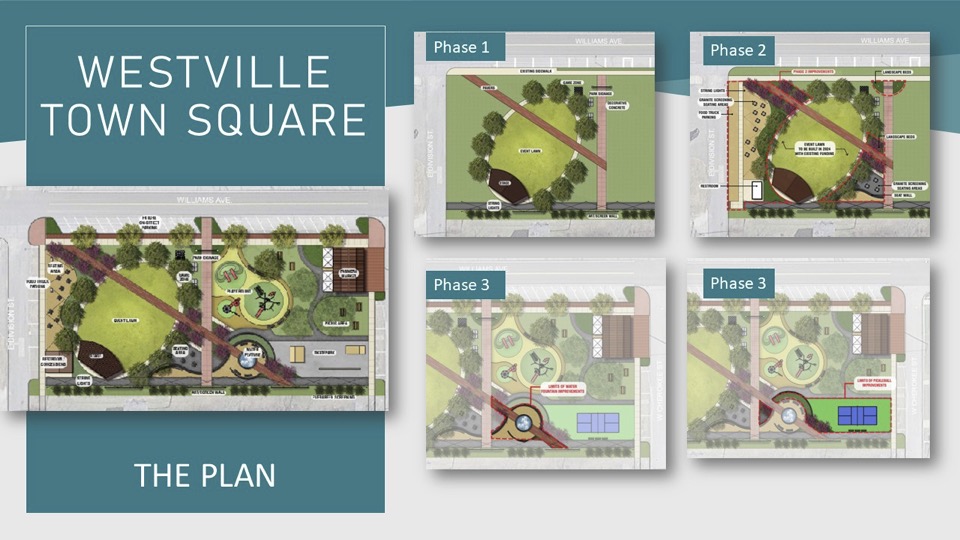

From there, Westville turned its attention to walkability, working with the University of Oklahoma’s Institute for Quality Communities to conduct a three-day community engagement session with residents and create a plan to turn a vacant lot into a town square. The university also provided a design for an improved downtown with a focus on walkability to connect the school district, town park, senior citizen housing, medical center, and other vital services.

The impact has been profound, bringing in new businesses, new housing, increased civic group participation, and future funding opportunities. These efforts, Stefanie noted, have inspired a pride of ownership the people of Westville are taking in their town.

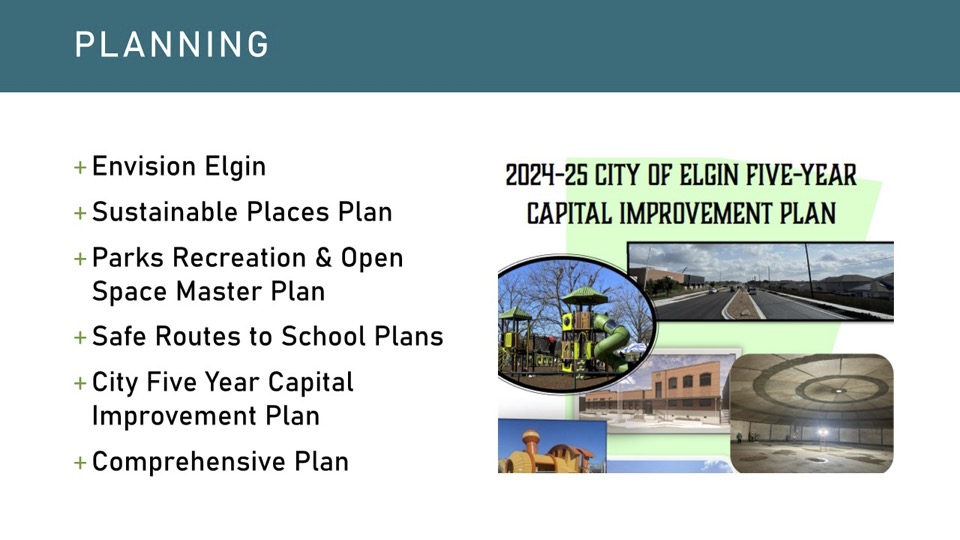

Amy shared a case study from Elgin, a small town located 19 miles east of Austin in central Texas that has spent the last 20 years focusing on improving walkability and downtown revitalization. One challenge of such efforts is when there are significant infrastructure ties to the Department of Transportation, such as highways that are unsafe and disconnect people from critical services and community ties. By prioritizing sidewalk construction, however, Elgin went from “good luck getting there” to better connectivity, including to transit nodes, as Elgin participates in a rural transit system that connects residents to Austin and other communities.

What was the critical piece of these efforts? The plans, including planning processes that allowed residents to envision what Elgin could be and share what they wanted to see moving forward. Combining those efforts with other plans, such as Safe Routes to School plans, allowed for better connectivity over time to schools, neighborhoods, adjacent commercial districts, and parks.

Then there’s the need for ongoing community engagement. Beyond print and social media promotion, it’s about going to residents, not simply expecting them to come to you. Amy mentioned that meet-and-greets at coffee shops and school events are key to establishing those relationships and obtaining community buy-in — especially when it comes to shifting public attitudes toward walkability in rural places where driving is the default.

During the Q and A, Stefanie also addressed the need to shift attitudes by involving the community in the planning and development process. “People want to feel like they’re part of that story.”

It’s also about stepping back and looking at the community’s values, added Shane. Every decision we make about the right of way is important.

The panelists also touched on audience questions about funding for small town development that supports walkability, particularly in the current federal funding environment. They stressed that building a coalition of partners can support both the success of planning efforts in communities as well as competitiveness for federal funding. There’s also the potential to identify additional funding sources by engaging with local and regional partners.

Westville, said Stefanie, banded together with three other small communities to apply for and win a Safe Streets for All grant, and partnered with the University of Oklahoma to conduct community engagement.

The best way forward is to “keep planning and keep building partnerships,” encouraged Shane. “Reach out to regional partners — universities, banks, Tribal governments… Make progress [and] keep working to stay competitive for federal grants.”

For more, watch the whole webinar here!

Additional Resources

- Navigating Main Streets as Places: A People-First Transportation Toolkit

- Town of Westville, Oklahoma, Master Plan

- Streetscape Design & Pedestrian Network resources — Main Street America

- Transportation Matters for Main Streets: Community resources — Main Street America