Let’s take a minute and talk about the past, present, and future of walkability. If you found yourself in last week’s webinar or on this blog, it’s safe to say that you are likely an advocate for green spaces and walkable communities. What if urban planning considered pedestrians rather than vehicles to create more walkable and inclusive neighborhoods? Are we likely to see more green spaces, crosswalks, sidewalks, and bike lanes? The data says yes!

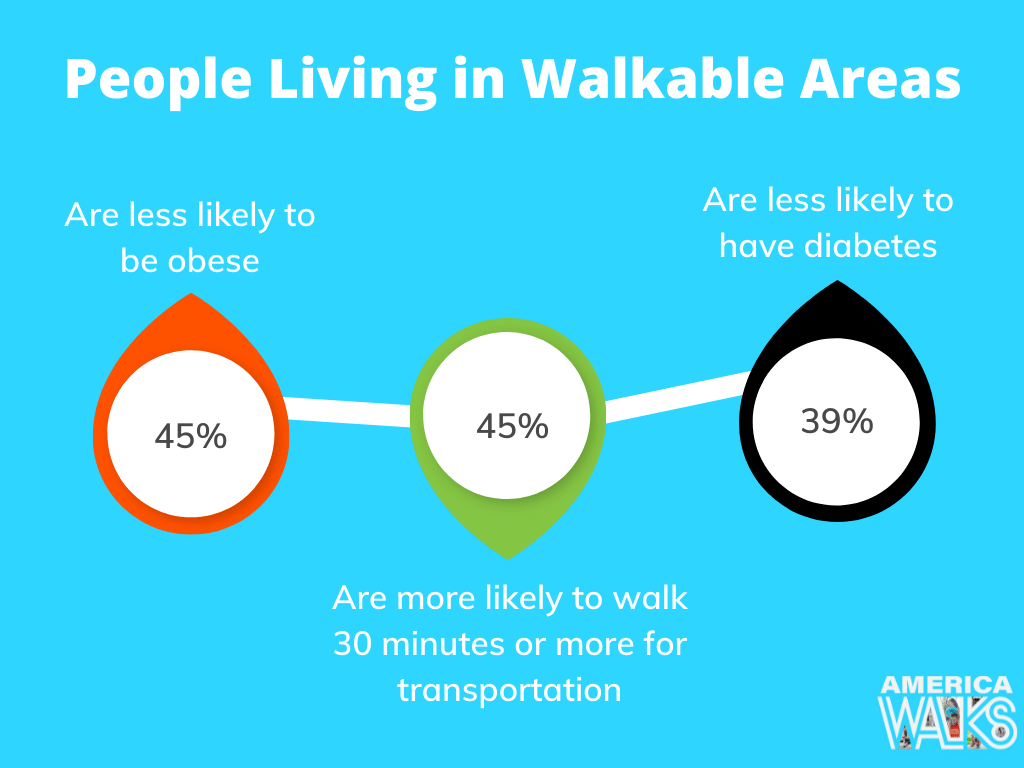

The data also shows that when our current urban environments lack these infrastructures, it can be linked to high rates of stress, lack of social interaction & community engagement, and obesity. People in this space like Dr. Lawrence Frank are not only trying to bring attention to these topics and how they intersect, but also change them in big ways.

Dr. Lawrence Frank is a professor at the University of California – San Diego, President of Urban Design 4 Health, and a board member with America Walks. He has studied land use and collected data on his findings for years and, in this webinar, takes us through some of that data to help shape the narrative around creating more walkable communities – while simultaneously making walking more equitable – and why we should continue to form coalitions around these issues as we shape and reshape our urban cities.

Watch the Full Webinar Here:

The Data Around Need for Walkability

“We have a lot of research saying that when you invest the infrastructure dollars into communities, especially those who are in need and underserved, causation is there.”

Dr. Lawrence Frank

Examples of what we can influence in the built environment are things like transportation infrastructure, land use & walkability, pedestrian environment, and green space. The current built environment we live in is modifiable, according to Dr. Frank.

Dr. Frank has been researching the topics of land use and walkability for decades and his data proves the positive impact of sharpening our focus on walkability in urban planning and development. His work has been cited countless times and even led to the development of WalkScore, something many of us have used. His work aims to show the intersectionality of urban planning and development with equity and public health – a connection that hasn’t always had mainstream discourse.

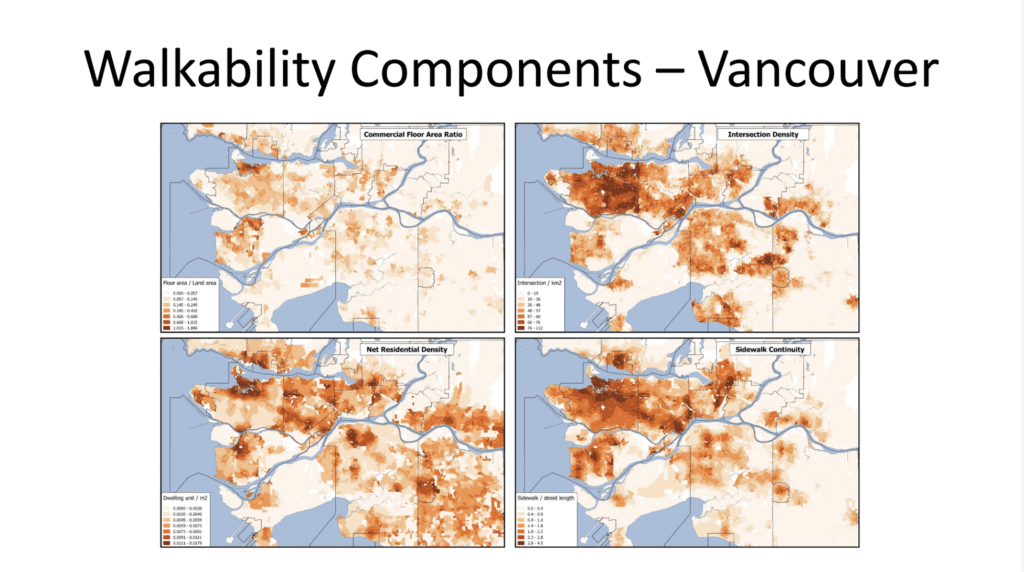

Dr. Frank’s work is now measuring changes in walkability – particularly in Vancouver, British Columbia. This is fairly new data being collected and built out to measure walkability components such as sidewalk continuity which shows where sidewalks exist and where they don’t. Imagine being able to pull up Google Maps and see all the sidewalks in your city to plan your walking route! That could be our future with the help of Dr. Frank’s work.

Some Quick Stats on Walkability and Health

According to Dr. Frank:

“Mental health is more and more understood to be related to the environment. The environment we live in not only affects our physical health but our mental health.”

The Three Geographic Scales

When looking at cities for walkability, Dr. Frank breaks down regions into three sections – regional accessibility, walkable complete neighborhoods, and pedestrian environments.

- Regional accessibility shows the macro lens of a region, meaning the transit we take across town to get to our jobs, etc.

- Walkable Complete Neighborhoods is the idea of being able to live, work, and play all within walking distance.

- The pedestrian environment is the micro-scale of a region where infrastructure dollars target projects such as good sidewalks, seating areas, street lights, and more.

Walkability and Social Justice

One of the biggest takeaways from Dr. Frank’s work is that walkable areas are not equal for all groups and vary based on demographics. Frank explains that “wealthier [neighborhoods] have green-space, shops, entertainment, other destinations. Where the poor [neighborhoods] have air pollution, noise, crime, and injury risk with none of the benefits.”

For years, land use patterns created inequities across our cities, much of which we still see today. Today we see predominantly poor communities and communities of color with fewer benefits from walking than their more affluent white counterparts. Dr. Frank and others in the field are working on different modalities of measuring inequity in walkability and how to close that gap in the future of urban planning and development.