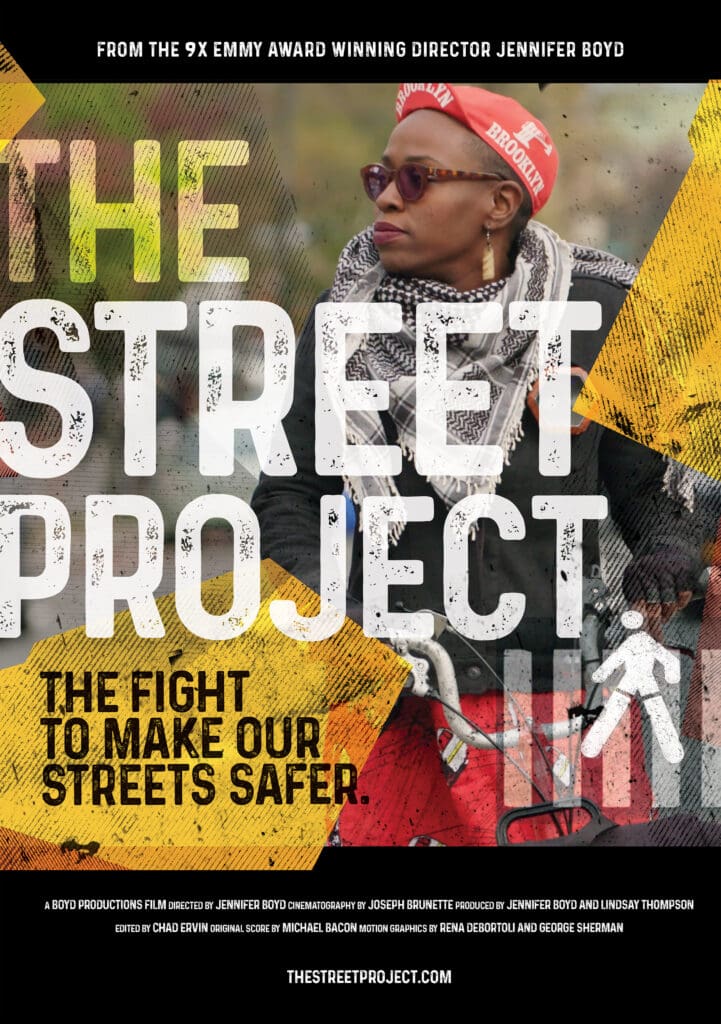

I recently watched “The Street Project” documentary and interviewed its director, co-producer, and writer Jennifer Boyd. It is available for local screenings and has been used as a tool to spark conversation about safe streets in over 50 cities so far. Here is my interview with Jennifer, edited for clarity and length.

Mike McGinn:

I am Mike McGinn. I’m the Executive Director of America Walks. And I have with me today Jennifer Boyd. She’s the director, co-producer, and writer of The Street Project, which is a movie I’ve watched a couple of times, but I’m not going to describe it to you. I’ll let Jennifer do that! Jennifer, what is the Street Project?

Jennifer Boyd:

Well, Mike, thanks so much for being willing to chat with me about this. The Street Project is a documentary about the global grassroots movement to take back our streets, our largest public spaces, so that they are accessible to all, to all kinds of transportation, all kinds of needs. I think that that might sound like a preachy, dull topic, but when you think about the ways that every aspect of our lives is connected – our community, our neighbors, how we get from one place to another, how we relate and have the opportunity to connect with people, what is a common denominator in all of that? It’s our streets. It’s how we accidentally meet people, it’s how we move about, it’s our opportunity to connect with others. And so it actually is an unbelievably fascinating topic.

Mike McGinn:

Well, you know, you can guess that I’m convinced because I’ve been working on active transportation issues for a while, and there’s something about it that really pulls you in. Once you see how we build things and then you start to ask why, how can it be different? It’s a pretty deep topic. Tell me what motivated you to make the documentary.

Jennifer Boyd:

Well, so a few years ago, I had done a documentary called 3 Seconds Behind the Wheel, and it was a look at distracted driving. And we put cameras into cars and monitored people’s behavior over six months. It was absolutely fascinating; it was really at a time when those kinds of cameras and sort of that voyeuristic look at behavior wasn’t so popular. So it really captured people’s attention.

Anyway, that was distributed through PBS, it’s online now, and after that project was finished, I thought, well, why not look at the other half of the transportation fatality issue? If half of all fatalities happened outside of the car, aside from the driver, to pedestrians and cyclists, why not look at the other side?

And I thought, alright great, I’ll look at how distraction impacts pedestrians and cyclists. Well, we got some funding to do that. And a few seconds into real research, hardcore research, and I realized, wait a minute, distracted pedestrians walking into the middle of the street staring at their cell phones and hoping for the best – that really isn’t a thing. That really is such a small part of all the fatalities and the skyrocketing of this issue.

So my topic has nothing to do with distraction and of course, as a lot of people know, everything to do with design, the design of the streets, the design of cars, speed behavior, how we value and think about pedestrians and cyclists on our roadways and a whole bunch of other topics and how the way we look at who gets to use our roads.

I was working with the city of New York and they were giving me all their security camera footage. They were very generous. And I’m trying to figure out human behavior and thinking about monitoring the streets. And what do these people, you know, what’s the common denominator and how they’re behaving like that leads them into the streets. And, you know, I was totally wrong. So with the benefit of being able to take time and really do the research and not try to find the quick answer that tells the story, I was able to really delve in and this is such an interesting project because I was sort of learning as I was going. I was really learning with the viewer all along the way. I continue to learn now with the viewer as The Street Project becomes its own life force. It’s all it goes out and it’s on PBS, but it goes out into the community and communities are using it as a conversation point so that they can address issues that are specifically important to them.

But the other thing I wanted to say is when I started this project, I didn’t want to make another piece of content in the media that was negative – that people just want to go, “Oh no, I’ve heard enough. I don’t want to hear anymore. I just want to bury my head in the sand at this point, there’s just so much negativity out there”. So then, you know, how do you make a documentary about pedestrian and cycling fatalities and not make it negative? And that’s where I think I’ve created something that is good storytelling and really hopeful because we follow people who are trying to make a difference and their stories are really interesting.

Mike McGinn:

I was going to say that you mentioned preachy earlier, and I want to say I’ve watched it twice now – a month ago and then just before this to make sure I was ready. And, you know, the fact that you’re telling the stories of individuals and their experiences on their streets and how that moved them to action, I think that personal storytelling does change it quite a bit.

And of course, the protagonist at the beginning was an individual who was biking and hit by a car, her mother was hit while she was walking and how that opened up her eyes and how she ultimately became an advocate. I think the storytelling was pretty powerful. Now, of course, there was a certain amount of explaining. You had some really great experts as well.

We’ve designed a system that has really fast cars moving through places where people are present. And it’s an extremely dangerous mixture. And it’s designed that way on purpose, as you pointed out. And how do you get the people in charge of the design to change things rather than them simply throwing it back on the individuals using a dangerous system?

Jennifer Boyd:

Yeah, I was never somebody that I wasn’t in the field, I do lots of other documentaries on other topics, so I didn’t know – I didn’t have any preconceived idea of what the struggles were and what kind of story to tell. So one of the experts – and it really stuck with me – was this concept of democratic streets. Now, most people and many people have told me this afterward, I didn’t know this was a story I even needed to care about.

They would look at me and say, The Street Project. Oh, great. Okay, it’s about our streets. Okay, so cars speed, whatever. And they’d look at it and go, “Wow, I didn’t know this was a story I needed to care about.” And for me, what really struck me was this concept of democratic streets. They really are our largest public spaces, and we pay for them. We all pay for them. And yet we don’t really have equal access to their use, right? We have this preconceived notion that it should be used in one certain way. And as one of the historians in the film talks about, well, that’s not really what our history was, that’s not really how we used streets in the past. And so if we go back not that long ago, we will see that it certainly was okay for people to walk in the streets or for other types of vehicles to be in the street.

Mike McGinn:

Yes, the story of cars taking over the right of way that previously had been used by everybody in all different modes. By the way, my dad grew up in New York City, son of immigrants. He was what was called a three sewer man, which was the ability to hit a punch ball the length of three sewers on a New York City street. I don’t know if that still exists anymore, but street games were a thing. You grew up playing in the street. And so, you know, the very idea of the playground was because the street was no longer available.

And certainly, then that becomes an obstacle because very few people can remember that era anymore. What we see is what we think is normal now. In creating the film, what do you think are the biggest barriers to making these changes?

Jennifer Boyd:

So one of the great things about this film being used in communities to create, to gather people, and to have conversations about issues that are specific to their community is the fact that the barriers are different in different communities. Now, we all may know that narrower streets slow down traffic or we may know that protected bike lanes will bring out more women and children who will then feel safer to bike. And, you know, especially if you’re in the field or you’re now studying it, we all have these sorts of preconceived ideas and research about what works and what we believe works. But I think the barriers are that people are afraid of change and maybe afraid is too strong of a word.

But, you know, the unknown is – I feel for politicians actually, that you have to please so many people. I often think about the story of advocates like Transportation Alternatives trying to put bike lanes on the Upper West Side and people just being so angry because they couldn’t park their cars easily. After a while of seeing that it really did work, that the parking was okay, that there were more people biking, and that it became a win-win over time, it sort of dawned on me that this really can be the struggle of something one day. Finally, you can’t park in the spot that you always wanted to park in because now there’s this bike lane and you say, well, why are the bikes here? Or how many people really bike or that kind of thing that, you know, it’s a different challenge for every community. And whether you’re in a rural community or a city or somewhere in between, there are different factors for everybody.

Mike McGinn:

I think there are a lot of things that are counterintuitive to people as well, you know? Well, first of all, I agree with you. I think the biggest barrier is that lots of times people feel something’s being taken from them. You know, the parking or the bus lane or the redesign that puts a turn lane in bike lanes and takes away travel lanes. They think something’s being taken from them. They react very strongly. Our experience in Seattle was – we’ve done dozens of those streets that way – those safety redesigns and there’s very little call for returning them to the old multi-fast, multi-lane, dangerous roads, people actually end up liking them. But yeah, it’s a very vociferous reaction. And even though I do think – we’ve done polling too – there is very strong public support for higher quality of life and walking, biking and transit, but it’s oftentimes not as loud as the voices for keeping things the way they are.

I was really inspired in the movie by the individuals in Phoenix walking from store to store, business to business to help build support for change and the footage you got there of how dangerous the streets were …you caught some things on camera. Tell us about that…

Jennifer Boyd:

That was really eye-opening for me as someone from the East Coast coming out to a Sun Belt city. And I remember the first my first day at the Airbnb that I was staying in, and there were lots of little lovely restaurants nearby and I wanted to go to a tacoria that was, I don’t know, maybe 100 yards from the house. And so I walked down the street ready to go. But the restaurant was across the street and I’d been driving all day and I was like, I just wanted to go for a walk. So I just walked down. It’s not that far. And I look and I realize that I am going to have to cross – I think it was seven lanes of traffic to get there and I totally wasn’t expecting this. And I looked both ways and I realized that I actually can’t get there, that I truly can’t get there unless I go back to my house, get in the car, and go around the block so that I can safely get into the driveway.

That was really sort of mind-blowing to me. And that gets back to the fact that having the film be a way for people to connect and figure out what the issues are specifically for their community. Having fast-moving roads in the middle of your city, your neighborhood may be one city’s issue, but it’s not another city’s issue, right? It may be just larger vehicles or whatever it might be.

So anyway, I want to stress that this is being distributed through PBS and all of that. But the most important thing really has been for communities to use it as this conversation piece. And you can get information at thestreetproject.com that tells you how to host an event and often people enjoy coming to it because it’s sort of a safe way for people to connect who’ve never been to, let’s say, a bike-walk event. They’ve never been advocates in any way. They may be hesitant because they’re not planners, they don’t know the stats, and so they don’t feel like they have enough background knowledge to come to a meeting or to make a difference in any way. And so they can safely come watch the screening, watch a show. And then often there’s a panel discussion afterwards, and that’s when they can learn a little bit more and make a decision for themselves about what is maybe how they can more effectively help or what to become more aware of what truly is the issue or are the issues in their community.

Mike McGinn:

What type of reaction do you tend to get at these screenings?

Jennifer Boyd:

You know, it’s really joyful. Now, I’m not at every screening. We just recently hit over 50 screenings around the United States. And we’re trying to push into states that we haven’t been in yet. And so, you know, obviously, people that are making the effort to come out are really positive and feel like it’s making a difference. And I do believe that. But I also find, you know, some people have said, especially since we’ve entered into a lot of festivals and so those folks aren’t like the choir.

And they’re very surprised because I often get, oh, wow, this actually was entertaining to watch and that means a lot for a documentary person because you don’t want it to feel painful, like, you know, this is medicine that they are required to watch this, so I have to watch it. So just in and of itself, if somebody feels like it’s not painful for them, I’m grateful. And then hopefully they get some background knowledge that helps them think about issues in the future or maybe make a difference in their communities.

Mike McGinn:

I’m a big documentary fan. There are lots of painful documentaries but this wasn’t one, absolutely not. You’re talking about the expertise issue -it’s an interesting thing. There’s a big problem out there, so somehow or another, maybe the experts don’t have it all figured out if we have that many people injured and dying every year. But there is that deference to authority oftentimes and it deserves to be questioned here.

Is there something that you filmed or did or there’s something you didn’t film? There are things you wish you could have gotten in but just couldn’t make it into the film.

Jennifer Boyd:

Of course. So two things that we can touch on are going to Copenhagen because it felt really stereotypical. And at the end of the day, my mind was blown because the reason I didn’t want to go to Copenhagen initially was because everybody thinks unicorns are bicycles. Of course, they’re everything.

Mike McGinn:

Right, [people think] Europe is special.

Jennifer Boyd:

Yeah, but as it turns out, they had the same problems that we did and they built roads and then converted them and they did it because it cost less. And so it’s a great, like economics story, right? And so there’s that and then there’s the COVID thing. So COVID was a huge factor in this project because we shut down production for two years. We had to cancel 30 days of shooting in four countries because COVID hit a couple of weeks before I was supposed to go to Europe.

And then everything changed. The way we thought about streets changed, the way we thought we could change a street changed. Suddenly we were able to close down streets and make them safe spaces for community gatherings without big meetings and zoning changes and all of that. And that gave me energy to tell a different story about how change is possible. But the things that I, you know, I wasn’t able to cover the rural story the way I really should have or could have if I had more time. You know, you can only cover so many issues. And clearly, there are so many tentacles to this topic. But, you know, we cover large cities, we cover some smaller areas. But the issues of rural communities – it’s a whole different game, but equally important and, you know, there are other countries I would want to go to. Other contrasts in how people think about transportation. You can see how it’s just tentacles, right? That’s why you do what you do! Your world of information can just expand and go in so many different directions, so there is so much to talk about.

So there are lots of regrets there, but you can only jam so much into an hour show, otherwise it just feels like a list. It’s not a story.

Mike McGinn:

Well, transportation and land use is so central, like, that’s the sense of place and places are so important to us. They’re so defining to us about how we feel and, you know, how we connect with other people, how we have a sense of belonging in the world.

And I think that crosses suburban, rural, and urban divides. Right? We all want to have places where we feel safe and comfortable and connected to our neighbors. And we’ve made it hard. We’ve made it hard to do that by designing places that keep us insulated from each other or not prepared to walk across the street or walk around and connect with each other as human beings. I think that was one of the biggest things about COVID. I think that it wasn’t merely the walking right that, wow, I need to get out of the house and walk around. It was like, I need to get out of the house and see other people. I need to connect in a safe way and streets were restored to a place that it happened easily because there was no work. Not every person would go into work, but a lot of people felt isolated and the street was where there was community.

Jennifer Boyd:

Absolutely! It was so dramatically different. And it does make me think, I recently was traveling and we used city bikes all the time and that is something I would have been terrified to do ten years ago. And now I do bike in New York City when I’m around and I was biking in this community that I was vacationing in. And it just sort of dawned on me about how liberating it was, how we were able to take a city bike pass. It wasn’t called city bike, it was a different kind of bike. And I think it was the equivalent of $15 for the month and your first hour of biking was free every day. So you can imagine how inexpensive it is then to get to the grocery store, to get to the library, to take kids to school, to visit friends. And if you can do that safely, then suddenly you have so much more economic power because of freedom and mobility.

Mike McGinn:

Yeah, I think the things that often come up, as a walkability organization, is people look at these suburban areas that have been designed where everything is so spread out, there are huge parking lots, there are wide streets, there are cul de sacs – so there’s not a street grid, like someone’s got to go out to the arterial and all the way around and back in again.

You have all of these things that separate people and one of the things that is going to change that is with the e-bikes and the e-bike revolution and big wide streets that already exist that are way too big for the amount of vehicles that actually need to exist. And I think this is also true in rural areas we’re seeing the person that lived two miles out of the town center, all of a sudden the e-bike becomes an extremely efficient way to go three or four miles and is more fun. But you need the safe infrastructure. So I do think that even though we’re America Walks, the idea that that that biking might be the way to get from place to place, that you can then walk around, I think they’ll connect. I think it will be really great at those places that have longer distances to travel and it’s not the urban area where there’s a really great concentration of housing and restaurants and jobs and services. But there’s certainly the room to do it if we can slow the cars and create safe infrastructure.

Jennifer Boyd:

Yeah, and I think there’s something to be said for that really. And it’s a challenging message that really has to be the single biggest challenge is the economics of it all. This idea that it’s either or that if you have bike infrastructure or good safe, walkable streets, well then you can’t afford to do something else where in fact, you know, we because we’re the choir here, right? We know that it costs less to build that bike infrastructure than it does to upgrade or add on lanes of road, but it’s the way you…

Mike McGinn:

Hey, my workbench in the garage has all the tools that I can get. I don’t have just one tool. It seems like some tools are better for some jobs than others, and treating it like a war between modes is ridiculous. It’s actually creating it so that I can use the right tool for the right job. What is the one big thing that you or maybe not the one big thing, but what would you like people to take away from this after they watch it?

Jennifer Boyd:

Yeah, I think that we’re all on the same team, that safe infrastructure benefits cars and it benefits bikes and it benefits pedestrians. I love cars. It can be life-changing. You get to go places you would never get to go. But there’s nothing like the freedom to be able to bike where and when you want to easily and cost-effectively or to walk. How healthy is that? And to have those choices, it just makes for a more vibrant, livable community.

So I know we’re running out of time and I just wanted to, you know, one more plug. If people are truly interested in creating a conversation in their community that thestreetproject.com has all the information, they can screen the whole documentary or sections of it and have community conversations around it, invite new people into their groups, they can use it as a fundraiser if they want to charge tickets, do it at a movie theater, a library, do screenings at home. And I do really appreciate you being willing to talk with me about it.

Mike McGinn:

Well, you anticipated my last question. One last plug, so but I’ll give it a plug thestreetproject.com, and it is a good documentary, it’s a great conversation starter. And if you’re looking for inspiration about how you can get engaged or some great stories being told in it as well. So thank you, Jennifer, and I’m glad to do that.

Jennifer Boyd:

I really appreciate your time. Thank you so much.