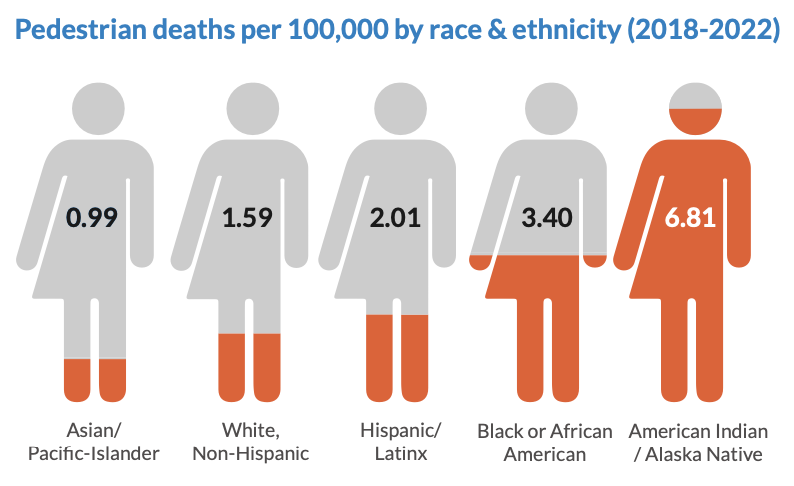

About 7,500 pedestrians lose their lives on America’s roads every year. This tragic reality disproportionately impacts communities of color, including American Indian and Alaska Native pedestrians, who are more than four times as likely to be killed while walking, compared to white pedestrians.

Speed is a critical factor in whether or not a collision is fatal. In most tribal reservations in rural parts of the country, vehicles travel at high speeds, and there usually are no sidewalks.

But large traffic-calming projects can take years to complete, cost millions of dollars, and often face heavy opposition.

Temporary quick-build projects are a way to address traffic and pedestrian safety issues quickly and cost efficiently. They also allow communities to experiment with solutions that are tailored to their needs.

Speaking with Experts

During a webinar on Quick-Build Projects in Indian Country, America Walks Technical Assistance Lead Ian Thomas led panelists in a discussion of a 15-month-long project to engage tribal communities and implement temporary quick-builds through a Road to Zero traffic safety grant from the National Safety Council.

Project partners included the Pueblo of Jemez, Cherokee Nation, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, University of Montana, and America Walks. Ian was joined by Hillary Mead, Primary Prevention Program Supervisor for Cherokee Nation Public Health; Sheri Bozic, Director of Planning, Development, and Transportation for Pueblo of Jemez; Samantha Morigeau, Doctor of Physical Therapy with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes’ Tribal Health Department; and Maja Pedersen, Assistant Professor at the School of Public and Community Health Sciences at the University of Montana.

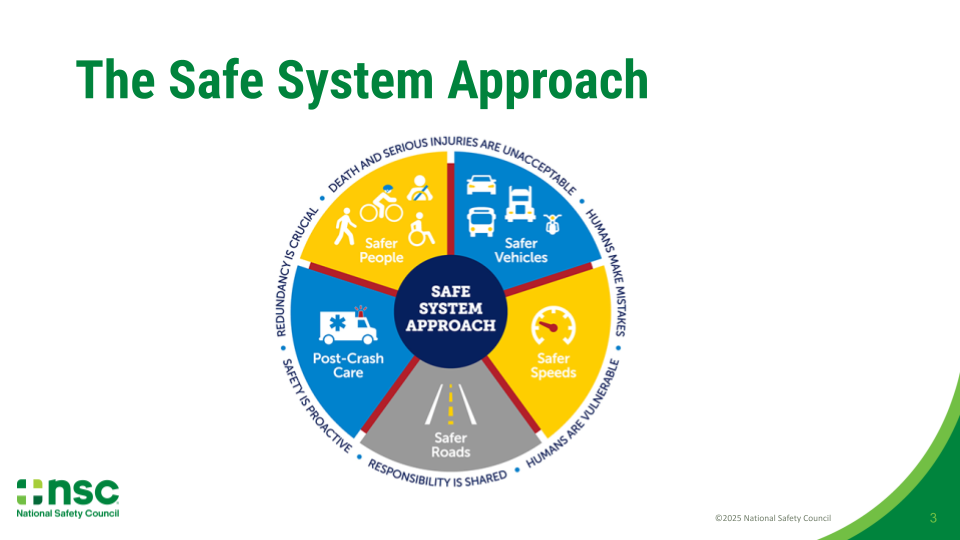

Julia Kite-Laidlaw, Senior Program Manager with the Road to Zero Coalition, kicked off the webinar with an overview of the National Safety Council’s mission to eliminate preventable deaths and injuries due to traffic in the United States through a Safe System Approach. “When it comes to what’s going to solve the crisis of pedestrian deaths on American streets, it’s not just one thing,” said Julia. “There’s no magic bullet. It’s going to be all these things working together. The more we can get communities involved, and the more that we can get people locally invested in what’s happening on their roads, the better.”

Cherokee Nation

In Kenwood, Oklahoma, which is located within the Cherokee Nation Reservation, over half the population is Native American. Traffic safety is a particular issue for the students of Kenwood Public School, which is separated from the Woody Hair Community Center by a fast-moving road.

Hillary described the process of planning and implementing a quick-build project to connect the school and the community center through a high-visibility crosswalk. Project leaders started by identifying road hazards, existing infrastructure, and observing traffic conditions. Preliminary assessments included a walk audit, speed checks, and traffic counts. They also conducted walk-and-talks and community surveys to collect data, as well as a cost-benefit analysis.

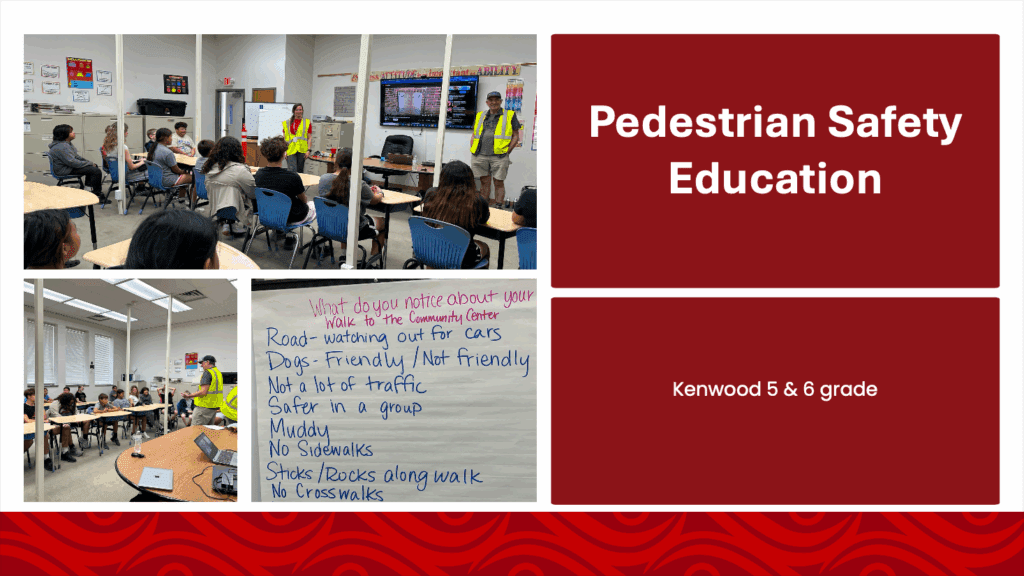

On the day of the quick build, project leaders led a pedestrian education session for Kenwood’s fifth and sixth graders. Afterwards, the students assisted in the quick build process. Volunteers installed planters, delineator posts, and pedestrian signage. Rainy weather prevented sidewalk painting, but that was done a few weeks later.

After the quick-build, project leaders conducted evaluation and feedback with the students and community. Overall, the corridor’s walkability score improved significantly, and survey respondents noted the new infrastructure.

Project leaders presented the findings to the tribal council and also submitted for broader funding. In July 2025, they received funding and started installation of permanent infrastructure along the road.

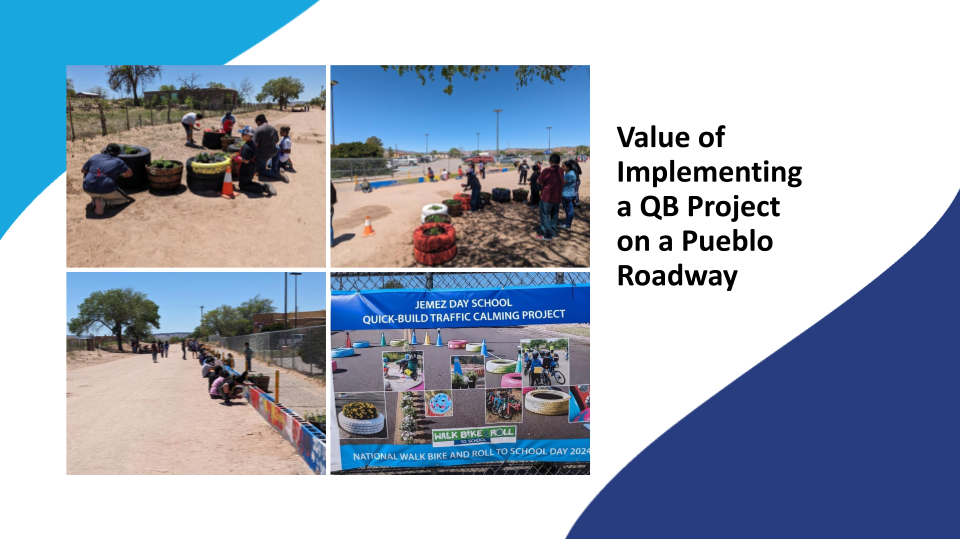

Pueblo of Jemez

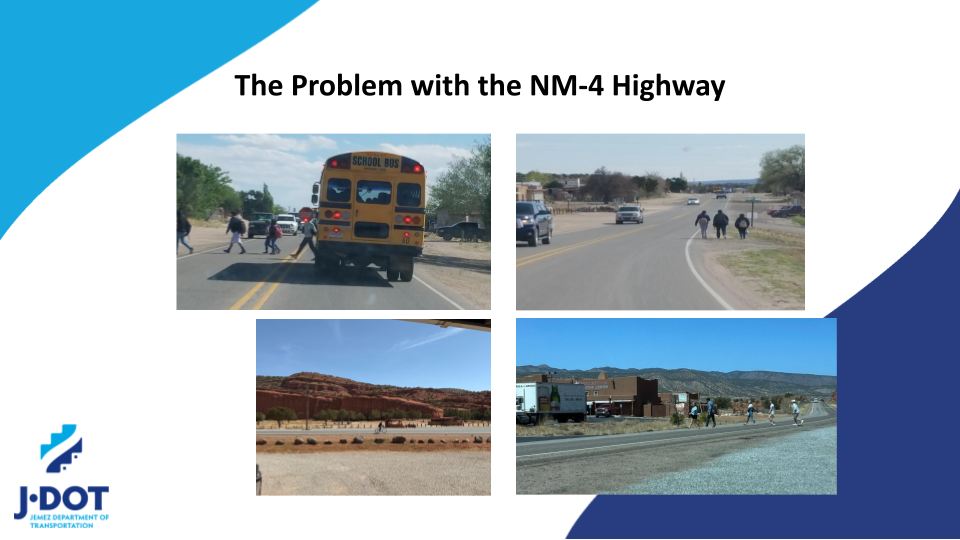

Sheri introduced the Pueblo of Jemez’s efforts to improve pedestrian safety on tribal roads. Located between Santa Fe and Albuquerque, the Pueblo of Jemez has a population of 3,900 and consists of three major non-contiguous land parcels. New Mexico State Road 4 bisects the main part of the land, running through the heart of the village and posing a significant threat to the safety and movement of residents.

While the Pueblo faced challenges in implementing initial plans for a project along the highway, they pivoted to quick builds as a way to address immediate concerns and build public support for permanent interventions.

One of the quick builds took place on Day School Road, a wide, fast-moving road in front of a Pueblo school that teaches Kindergarten to sixth grade. The project convened the students and community, with students painting traffic control devices, including planters with flowers. Since the project was completed, road speeds, previously two to three times the speed limit, have declined. The street also now has solar-powered speed feedback signs.

The second quick-build project addressed vehicle speeds and walkability on Sheep Springs Circle, a residential “loop” road and the site of frequent complaints regarding speeding vehicles. In April 2025, dozens of tribal safety professionals from across the country gathered with local residents for a workshop to complete a community road safety survey and assist in constructing two crosswalks. Residents, including a number of children from the community, measured and striped the crosswalks and installed a protected walking path along the road. Planters and sidewalk chalk art completed the redesign by providing visual elements to slow driving speeds.

The Pueblo is currently looking for opportunities for funding to make these projects permanent. Said Sheri, “That’s really the mission of quick-build projects: to set them up, get community feedback, see how it works out for improving safety, and then implement something more permanent in these areas.”

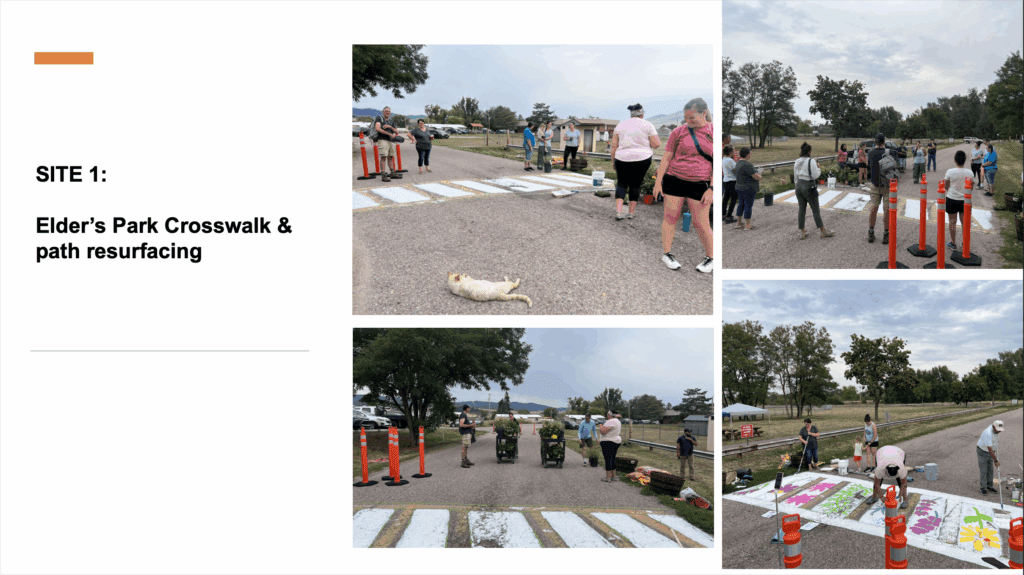

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes reside on 1.3 million acres of the Flathead Reservation. Of the 31,000 residents, 8,000 are Native American. 22% of the population living on the reservation are age 65 or older, which is higher than the national average. Lack of pedestrian infrastructure poses a significant safety challenge for this population.

Dr. Samantha Morigeau, who is an enrolled Bitterroot Salish tribal member, spoke on the Growing Older, Staying Strong initiative, a collaboration between Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes tribal health and the University of Montana to conduct community-based participatory research on the Flathead Reservation to promote physical activity among older adults.

Maja, a National Walking College fellow, discussed the Our Voice in Motion project, which used AARP’s Eight Domains of Livability as a guide to thinking about the relationship between transportation and public health. Using Stanford University’s Our Voice method, project leaders recruited and assessed older adults living on the reservation. Participants used a mobile app to document responses to prompts related to pedestrian safety and mobility. Within the app, participants provided photos, voice memos, and narratives about walking paths, crosswalks, and other infrastructure they came across in their daily lives. They also tagged submissions related to walkability, safety, street design, fall risk, weather, and other factors.

Project leaders presented the data collected from the app to five communities and asked older adult participants to add comments and discuss how to address walkability challenges. They also presented the data to the Community Advisor Panel for review and discussion before sharing results to additional stakeholders and policymakers.

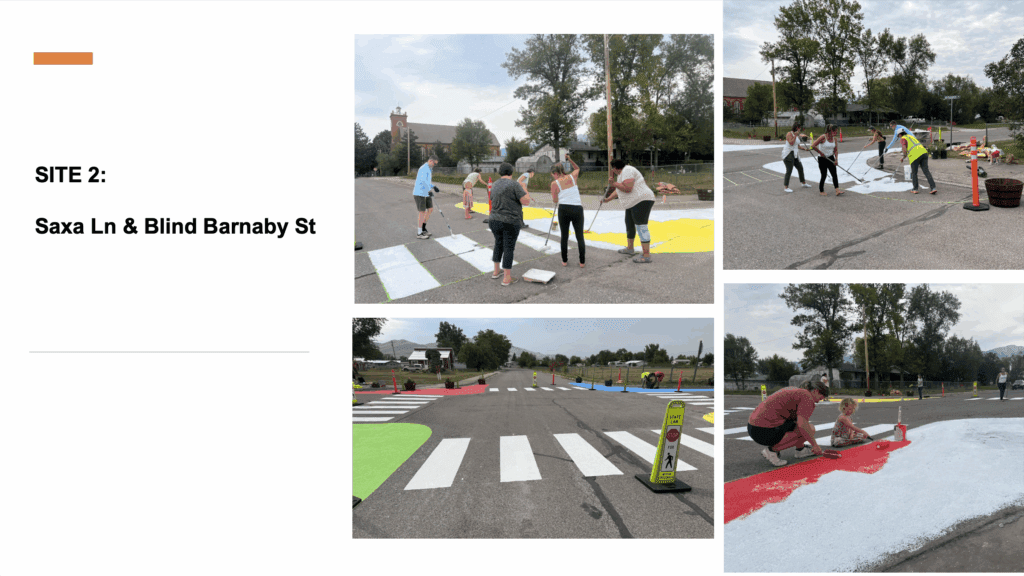

The quick-build project emerged from the results of Our Voice in Motion. Community feedback helped the project team choose two sites in St. Ignatius, Montana. The community came together at Elder’s Park to create a new, higher-visibility crosswalk featuring painted flowers that are culturally significant to the tribes of the Flathead Reservation. Next, volunteers addressed the intersection of Saxa Lane and Blind Barnaby Street, a four-direction intersection with no crosswalks. The intersection’s new bulb-outs were painted in colors corresponding to each season.

Q&A and Takeaways

During the Q&A, Sheri mentioned that while much work has already been done, there is much more to do to address highways built through tribal lands. Getting approval and funding for larger projects is difficult. Quick builds offer an opportunity to address concerns on local roads. Still, larger, more permanent interventions will require partnership with state departments of transportation, which can pose other challenges.

Maja discussed how transportation and pedestrian safety are both issues of public health. She also emphasized the importance of gathering data to legitimize the efforts of these projects to different stakeholders, as well as to communicate outcomes related to health, safety, and the mobility of children and older adults.

Dr. Morigeau echoed the sentiment, describing how she gained the support of tribal leadership by building the connection between transportation and public health. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes council members even asked the physical therapy department to be more involved as they build out skate parks, playgrounds, and walking paths.

Hillary spoke about the Tribal Pedestrian Safety Resource Library, which consists of fact sheets, public awareness campaigns, technical toolkits, sample policies, and training programs for communities and professionals.

To wrap things up, Ian provided details about the national network of tribal pedestrian safety advocates and professionals.

For more, watch the whole webinar here!

Additional Resources

- Quick Builds in Indian Country to Address Unsafe Road Design

- Pedestrian Fatalities In Indian Country: Responding To A Crisis

- A Policy Round Table Series: Pedestrian Safety in Tribal Communities